Worsening natural hazards an "opportunity" to rethink cities says Amy Chester

The increasing need to protect cities from environmental hazards is a chance to transform communities for the better, says Rebuild By Design managing director Amy Chester in this interview for our Designing for Disaster series.

Rebuild by Design began in the wake of Hurricane Sandy in New York as a competition run by the US government to instigate projects that would ready the region for future extreme weather events.

A decade later, the now independent nonprofit works with municipalities around the world on climate resilience and is sought after for the community-rooted approach that it pioneered in the Hurricane Sandy Design Competition.

"We don't come with any answers"

The organisation's collaborative working process, which engages a wide range of stakeholders, is "definitely a big piece" of what makes Rebuild by Design unique, says Chester, who has been managing the organisation from the beginning.

"The second one is that we don't come with any answers," she added. "We come with questions and we research everything together."

In the Hurricane Sandy Design Competition, that meant that entrants didn't pitch a project or a vision. Instead, they pitched themselves as teams of professionals from various backgrounds.

From 150 international applicants, 10 groups were chosen to participate in a collaborative research phase, which involved touring the Sandy-affected region, meeting affected people and eventually presenting multiple concepts for interventions that could make a difference in the face of future climate events like flooding and hurricanes. Selected architecture firms included OMA, BIG and WXY.

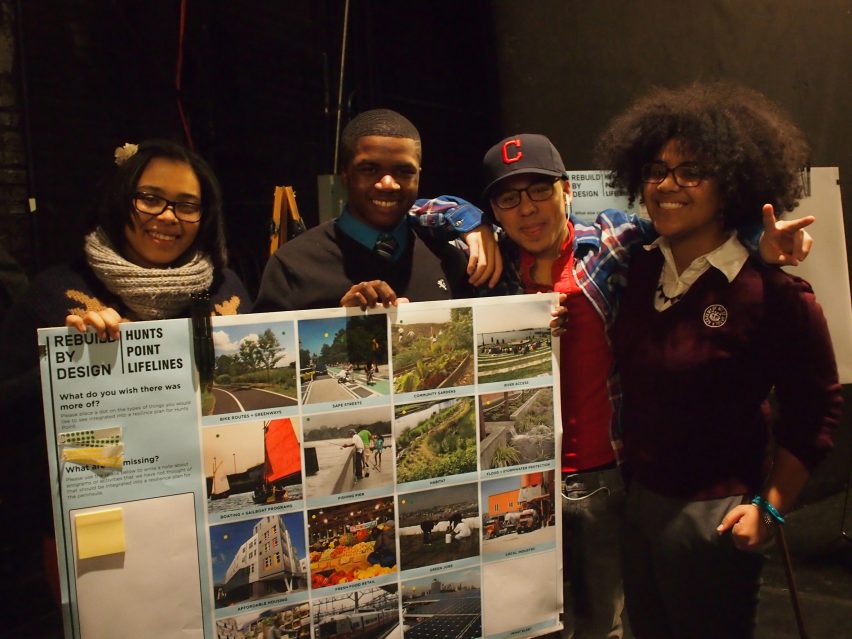

Ten of their concepts, one per team, were selected by a jury for funding and gradually developed into fully fleshed-out projects, again using collaborative approaches like workshops and community outreach events.

"We kind of turned transparency on its head by inviting those most involved to the table from the very beginning, to actually create the table together," said Chester.

Collaboration and transparency are not just buzzwords for Chester. She advocates for more genuine candour in communication between governments and their citizens in the face of climate change.

"Every single city has to understand what their own risks are and really have conversations with the population about how much risk are we willing to take on," she said. "You can completely fortify your city and say, 'We don't want any risk', or you can say 'hey, you know what, it's okay if we flood six inches, or two inches, or a foot, or whatever it might be'."

"Then you can design your adaptation practices to meet that risk," she continued. "If you don't have those conversations out in the open, then communities just feel that their government will protect them 100 per cent and they're floored anytime that there's a climate event and something happens to their homes and their livelihoods."

Best climate-resilience projects "help us on wet days and dry days"

Projects to have come out of Rebuild by Design include Scape's 2023 Obel Award-winning Living Breakwaters coastal defence system, which helps calm the water around Staten Island while fostering marine life, and BIG's Big U, a horseshoe of raised parkland, floodwalls, berms and sewer system upgrades encircling lower Manhattan.

For Chester, the most important climate-resilience projects are situated on a community level not an individual building level, and improve public space as much as they protect people from the elements.

"If we're doing it on a community scale that means that everybody is participating, everybody is excited about the outcome, and you are creating interventions that aren't only for climate change — they can also be enhancements to public space," said Chester.

Her favourite example of a place that has done this well is the city of Hoboken, across the river from New York City in New Jersey.

There, the Rebuild by Design-funded project titled Resist, Delay, Store and Discharge, by OMA, complements the city's plans to build a series of interconnected resiliency parks to store stormwater, three of which are now open and the last of which is under construction.

The interventions have not only helped alleviate flooding in the city, which is mostly built on a flood plain, but they have delivered on community requests for infrastructure like safer pedestrian crossings and bike lanes. The improvements are credited with cutting the pedestrian death toll down to zero for four years running.

"Ten years ago, I would have never said that a landscape architect is on the frontlines of climate change, but they really are," said Chester. "And so are architects."

"It's really about leveraging the opportunity that we have at this moment to rethink our communities and do it in a way that will help us on wet days and dry days and everything in between."

Most current building still "something that we're going to have to fix later"

Chester still sees many flaws in planning and design for disaster prevention. There's a failure to consider heatwaves — what Chester calls "the silent killer from climate" — as a natural hazard in the US, which means mitigation is underfunded, while too many developments are being built without measures to protect them from events like flooding, because they're not seen as being at risk.

Homes in recognised floodplains are built to set standards, said Chester, but those standards are based on the frequency and intensity of events in the past, not predictions of what is to come in the future. And homes outside of those areas may have no adaptations, even though they are vulnerable.

"When we aren't creating something that is thinking about the future, we are creating something that we're going to have to fix later," Chester said. "Already 50 per cent of all floods happen outside of a floodplain."

On the positive side, she considers that the last two years have brought a change in how disaster relief and prevention is understood in the USA, with a shared understanding that events are on the increase.

"There's just something about the past two years that feels very, very different," said Chester, citing the passing of the Environmental Bond Act by voters in New York in 2022, making US$4.2 billion in funding available for climate-resilience projects, as a key moment.

And although she is worried that recent rhetoric from the UK government "that decarbonisation costs too much", marked by a U-turn on net-zero targets, is about to be replicated across the Atlantic, for now she considers there is unity in the US on at least the question of adaptation.

"Republicans may use the word weather and Democrats may use the word climate, but we're talking about the same thing," she said. "Everybody's communities are suffering and everyone is experiencing it."

The photography is courtesy of Rebuild by Design.

Designing for Disaster

This article is part of Dezeen's Designing for Disaster series, which explores the ways that design can help prevent, mitigate and recover from natural hazards as climate change makes extreme weather events increasingly common.