Tredje Natur proposes floating car parks to prevent urban flooding

Next in our Designing for Disaster series, we spotlight Pop Up, Danish studio Tredje Natur's bold proposal for cities to build floating car parks on top of flood-preventing reservoirs.

Pop Up is a response to the fact that dense cities, notably Tokyo, are building enormous underground cavities to defend against flooding, while at street level precious public space is being taken up by parking lots.

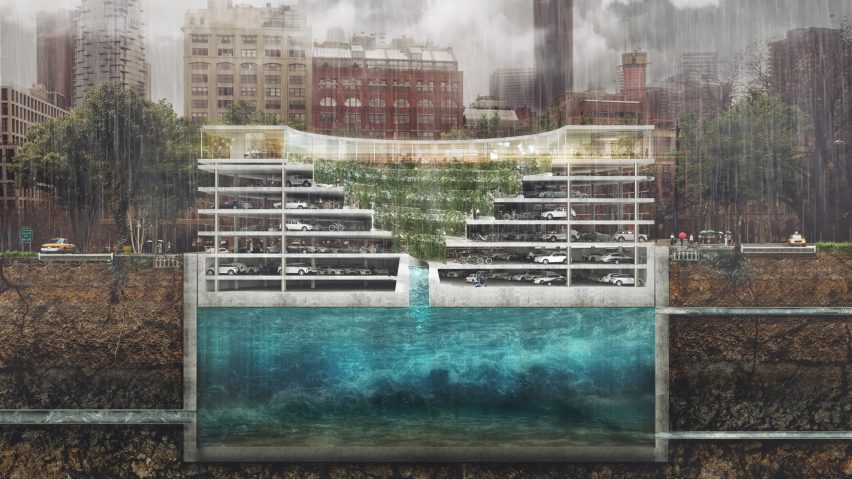

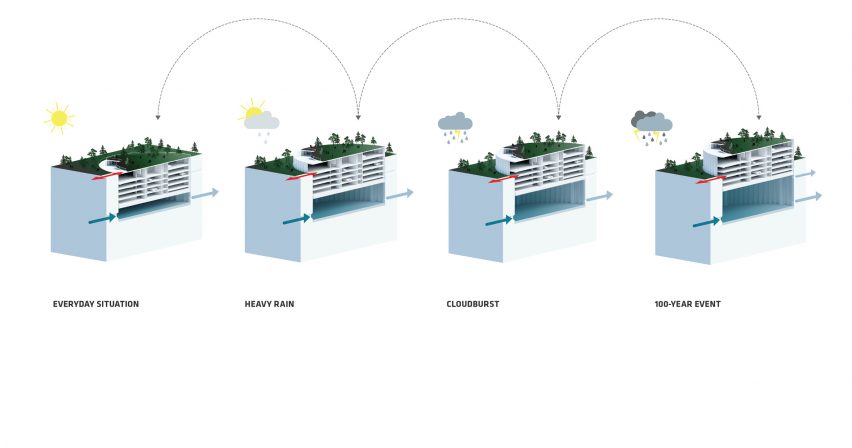

The concept would see a parking structure sunk into a hole in the ground. During extreme rain, the basin would fill with water, pushing the car park up above ground level.

Tredje Natur imagined the structure, for which materials are not specified, as a spiral shape that would ensure drivers could exit at all levels, no matter the height of the car park. It would also shelter a public garden on the roof from surrounding noise.

In normal weather conditions, the public garden would be accessible at ground level with the parking underground.

Studio co-founder Flemming Rafn told Dezeen that Pop Up represents the level of experimentation required to adapt cities to worsening extreme weather events.

"It's needed because we're in a crisis," he told Dezeen. "It is kind of pragmatic."

As well as providing social benefits, Tredje Natur contends that Pop Up would be cheaper than building flooding and parking infrastructure separately.

"On one plot we're establishing a big box of nothing that might stay dormant for 50 or 100 years, and on the very next plot people are arguing over a parking structure where the landlord wants to build overground because it's much cheaper and all the local neighbours and the city want to push it underground to have a public park," said Rafn.

"Taking these two and putting them together is just much more societally sound, and construction-wise, the budgets of the two structures are overlapping."

Tredje Natur is the most experimental of a number of Danish architecture and landscape architecture studios exploring ways to prevent flooding.

Denmark has emerged as a world leader in the space, after a freak flash flood in 2011 caused more than $1 billion of damage to Copenhagen in just two hours. Tredje Natur was founded in the same year.

"We just saw the need for trying to look at things differently," said Rafn. "Actually a lot of our projects are really simple."

"We were sleeping comfortably up until 2011," he added. "That was what accelerated the Danish movement towards more resilient urban-planning practice, but we really started from scratch."

The city of Copenhagen published a Cloudburst Management Plan in 2012 aimed at improving flood resilience.

Climate change means the Danish capital is under increasing risk of both flooding and drought, with what today constitutes a 100-year event likely to be more like a 10- or 20-year event by 2100, according to Rafn.

"We need systems that can somehow take the edge off these extreme events," Rafn said. "So we need to think in a much more pragmatic way, but also a bolder way, because there's no way of applying [existing] legislative approaches to these situations."

In the 19th and 20th centuries, engineers focused on sanitation prioritised pushing water into underground sewers.

But today these systems are struggling to cope during severe weather events – and building more deep subterranean infrastructure such as sewers is prohibitively expensive.

"We don't really see managing water underground as a feasible response to an extreme climate situation," explained Rafn.

Instead, Tredje Natur's projects often seek to deal with rainwater as soon as possible after it falls, including by letting it flow into areas designed to flood.

For example, in 2019 it completed a renovation of the century-old Enghaveparken urban park in Vesterbro to make it capable of holding 23,000 cubic metres of water.

The terrain slopes gently down towards one end surrounded by a short wall, where pneumatic flooding gates pop up to seal the barrier when water gathers on the ground.

Another Tredje Natur project is Climate Tile, a permeable paving system that allows water to filter down into an under-surface drainage channel before being directed to urban planting areas or being captured for street sweeping.

A 50-metre stretch of Climate Tile paving was laid in Copenhagen's Nørrebro neighbourhood five years ago, and Rafn said it works "completely as expected".

Rafn is adamant that the solution can be easily fitted in cities across the world as part of the routine maintenance of sidewalks and drastically reduce the cost of water management, but adoption is slow.

"No-one in the building sector is against innovation as long as it's been tested for 20 years," he deadpanned.

As its first project, Tredje Natur also produced the masterplan for the St Kjeld's Quarter "climate district" currently being constructed in Østerbro.

This 100-hectare neighbourhood has been touted as "the first climate-change-adapted urban area in the world" and is intentionally designed to flood during heavy rain.

The studio is now working on Lynetteholm, the controversial 280-hectare artificial island planned for Copenhagen's harbour intended to act as a massive storm-surge flood barrier while also housing 35,000 people.

Rafn argued that projects of this magnitude are necessary to prepare cities for more frequent and more ferocious natural hazards.

"I feel that we are approaching some of these extreme situations with too many small steps within existing scopes of sustainable urban transformation," said Rafn.

"We need to take larger leaps and devise more systemic, large-scale solutions or we will just see the price of these crises expand almost exponentially as we go towards 2100," he continued.

"The incentive to get going in any city is here and now. You don't have to go through the stupidity of sitting on your hands and hoping it's probably going to be okay, because it's not."

The images are by Tredje Natur unless otherwise stated.

Designing for Disaster

This article is part of Dezeen's Designing for Disaster series, which explores the ways that design can help prevent, mitigate and recover from natural hazards as climate change makes extreme weather events increasingly common.