Production designer Patrice Vermette put himself "in the position of the architect" for Dune

Brutalism, septic tanks and a rejection of the sci-fi status quo informed the set design of the film Dune: Part Two, production designer Patrice Vermette tells Dezeen in this interview featuring exclusive images.

Vermette worked on both parts of the movie Dune, an adaptation of Frank Herbert's 1965 novel realised by director Denis Villeneuve.

The second film continues to explore the book's themes of colonialism, environmentalism and religion as its warring factions battle for control over the resource-rich desert planet of Arrakis.

Villeneuve and Vermette – who also worked together on Villeneuve's science fiction movie Arrival – focused on creating a rich and original visual language for the Dune films, which are set thousands of years in the future.

"What's fascinating about the book, for the design aspect of it, is that it doesn't give you all the answers," Vermette told Dezeen.

While Herbert gave detailed descriptions of the conditions of each planet, he wasn't as descriptive when it came to what specific locations looked like, leaving plenty of room for imagination.

"It gives you just the right amount of pieces of the puzzle to help you understand what the realities of those planets are," said Vermette.

The designer said that with such detailed descriptions of site conditions, he found he was putting himself "in the position of the architect or the founder of that place" in order to meet a brief outlined by Herbert.

For Arrakis's capital city of Arrakeen, the design team knew there were winds of 180 kilometres per hour, unbearable heat, giant sandworms that are drawn to vibration in the desert sands, and that the Atreides' residence there is the largest ever made by humankind.

In response, the team created building facades imagined at an angle for the winds to sweep over, with thick rock walls to keep them cool, and the whole city is situated in a rocky valley between mountains that offers protection from the elements – as well as any monsters underfoot.

The buildings were also given a brutalist aesthetic, in reference to the way in which Soviet architecture was used "as a show of force" in regions it colonised.

Herbert's story takes inspiration from the Middle East, and different factions in it are often interpreted as representing the USSR and Western powers as they sought control of its oil.

"There's a conversation between the natural elements and what the different cultures are about, and you need to have a reflection on that to be able to start designing," said Vermette.

After the success of Part One – which earned six Oscars, including best production design for Vermette – the creative team had licence to go even bigger for Part Two.

Forty per cent more sets were built, and some 35,000 square metres of soundstages were used in Budapest in addition to several football fields worth of backlots and desert locations in Abu Dhabi and Jordan.

Among the most memorable new settings in Part Two is Giedi Prime, the industrial homeworld of House Harkonnen, which appeared minimally in Part One.

The Harkonnens – a brutal family line incensed at having been removed from control in Arrakis – are depicted in the film using dark and grotesque imagery, including a mountainous leader who bathes in viscous black oil.

"I was excited about the Harkonnens," said Vermette. "Denis always imagined a world that is repulsive."

Villeneuve requested a world that was "black and plastic" for the Harkonnens, and the oil became an additional textural element because of its relationship to plastic.

"It came from how Frank Herbert's book talked about overexploitation of the natural resources of Giedi Prime," said Vermette.

The inspiration Vermette needed to flesh out the Harkonnen homeworld for Part Two came when he passed a field full of black moulded plastic septic tanks while driving outside Montreal, where he is based.

It made sense to him that given the Harkonnens' character, that's where they would live. This aesthetic of black moulded plastic, combined with giant rib formations reminiscent of being in the belly of a whale and references to spiders and ticks, came to embody the buildings and machinery of the Harkonnens.

Septic tanks may be an unlikely starting point for an architectural language, but it's an example of how Villeneuve's vision can produce original results.

"The great thing about working with Denis is that he doesn't accept the status quo, which I love – meaning if we've seen it before, it's not interesting for him," said Vermette.

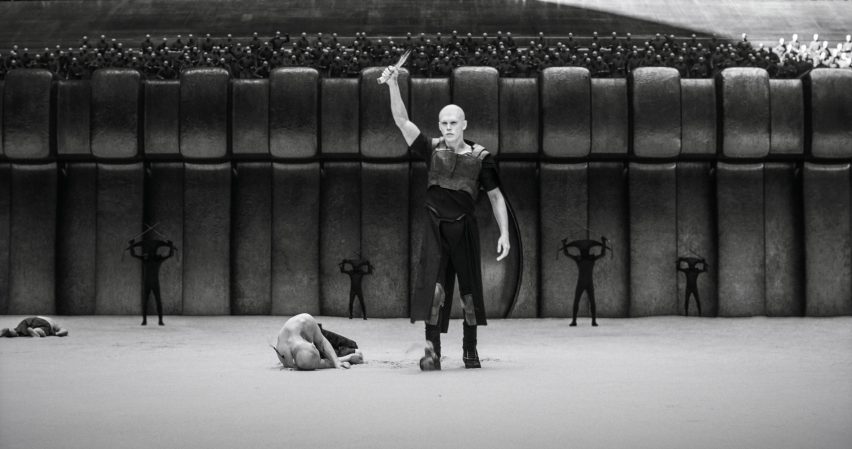

Giedi Prime is also home to the biggest set for Dune: Part Two: a battle arena similar to a triangle-shaped Colosseum, which was filmed with infrared cameras and desaturated to evoke the otherworldly look of being under the planet's black sun.

It was built using a technique the creative team had pioneered on the Dune movies for big sets, where only a relatively small part necessary for close-up and medium shots is built in detail – in this case, the arena's entrance.

The rest of the arena was completed with fabric-wrapped wooden frames representing the volumes of the building, which were then detailed with computer-generated imagery (CGI) in post-production.

The process aimed to block out natural light falling into the space and across actors' bodies in the same way that the walls or beams of the building would.

Otherwise, this alignment of light and shadow can be difficult to get right in post-production and becomes a telltale sign that visual effects have been used.

Although this approach was time-consuming, restricting filming to just a couple of hours a day when the sun was in the right place and keeping Vermette and his team constantly watching how shadows were cast, it enabled them to achieve the photorealistic look that they desired.

A final touch to the arena scene and the unnerving world of the Harkonnens are fireworks that appear like ink spatters rather than explosions.

"About 30 versions" of these fireworks were invented, according to Vermette, including one based on the structure of cancer cells, before the final design was chosen.

"It's a splotch of ink dropping on a glass surface," said Vermette. "It's like oil; it blends into the same type of aesthetics."

In contrast to the Harkonnens, another new world introduced in Dune: Part Two shows harmony with nature – even though that nature is the harsh and water-scarce planet of Arrakis.

This is the world of the Fremen, who live in "sietches" built into the rock. The descriptions of the Fremen in the book have been interpreted as referencing Arab cultures, particularly that of the nomadic Bedouin.

But for the film, Vermette said, "we did not want to borrow cultural elements from one culture in particular, because I don't think it would have been right".

Although the Middle Eastern references remain the strongest, they are combined with elements from the Mayans and the Aztecs – other cultures from the Global South that have faced colonisation, which Vermette says was intended to broaden this thematic exploration.

A third new world, Kaitain, the seat of the empire, was the only one to make use of a work of existing architecture: architect Carlo Scarpa's post-modernist Brion Tomb, a burial ground and garden in the mountains of Italy where concrete is sculpted with intersecting planes and geometric cutaways.

The Dune: Part Two team was the first to get permission to film there, although Vermette had already used Scarpa's work as an inspiration for settings in the first movie.

"On Part One, I was inspired by his architectural language for both Arrakeen and [Atreides home planet] Caladan," said Vermette. "But it makes sense that the aesthetics of the imperial planet influence the rest of the other planets."

"It's just like in real life. It dictates what's the taste, what's fashionable," said Vermette.

It's an example of how the film employs brutalism in a nuanced way – in some places stark and others poetic. Vermette particularly borrowed from Brazilian brutalism, which he says is "more sophisticated", as well as Scarpa's work.

"I've got a particular love for Scarpa, because I think it's his own world," said Vermette. "Maybe someone can say it's brutalism, but it's not really at the same time. It's really unique and distinct."

Photos courtesy of Warner Bros Entertainment Inc.