The Water Clock installation captures the "torturous experience" of waiting at an embassy

Architect Dima Srouji has used glass bricks to construct a miniature waiting room inside the Fenaa Alawwal cultural centre in Riyadh to visualise the bureaucratic limbo faced by displaced Palestinians.

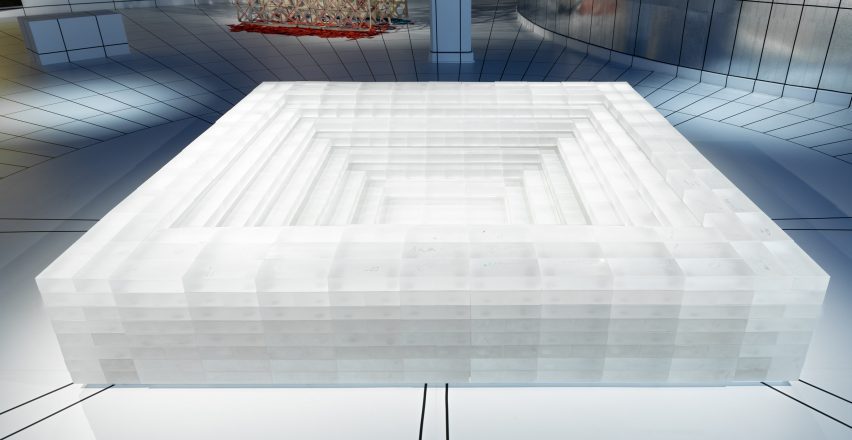

On show in Riyadh's diplomatic quarter, the scale model of an embassy waiting room combines tiered seating into a shape resembling a water clock – a kind of ancient hourglass that measures time through the flow of water rather than sand.

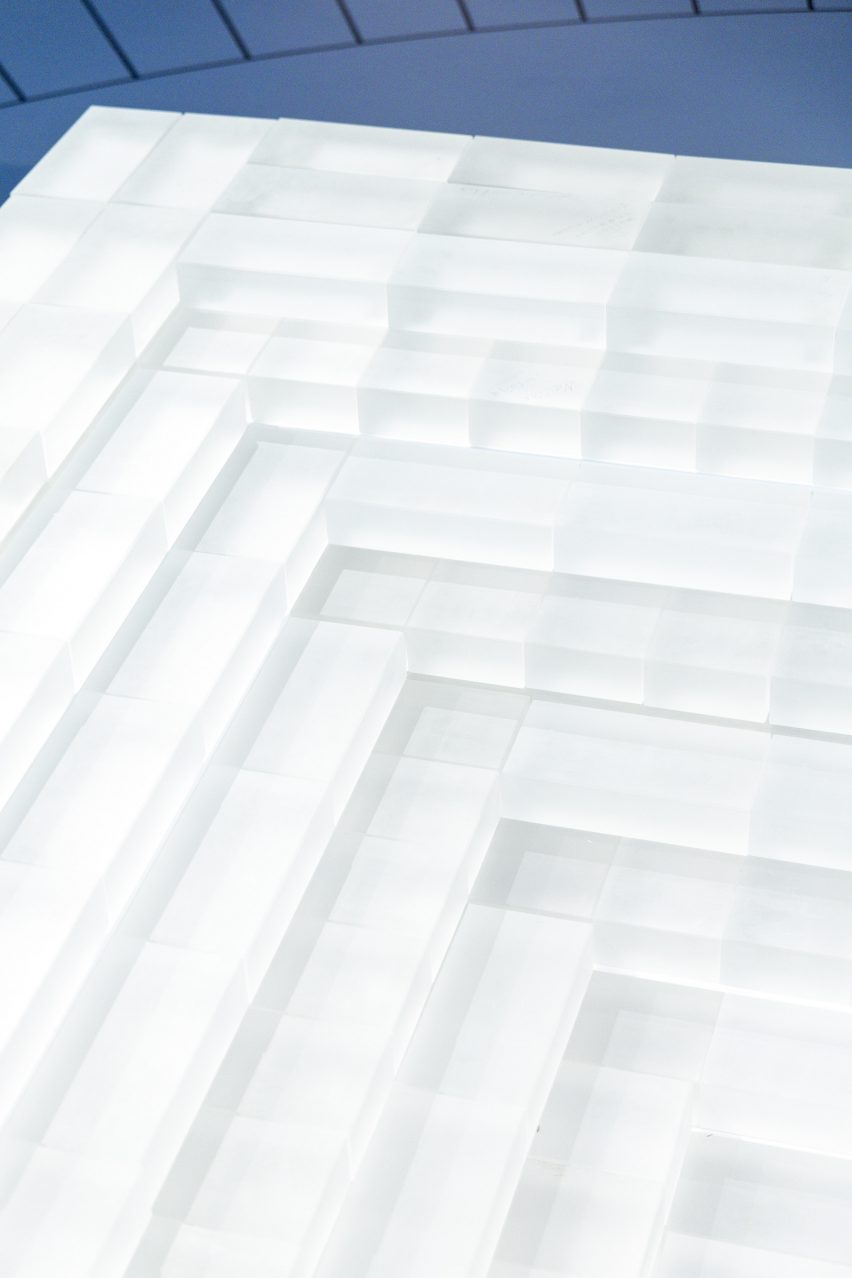

By constructing the installation from 812 frosted glass bricks, Srouji hoped to illustrate the experiences of refugees and people lacking proper documentation, who are forced to put their lives on hold while waiting on official paperwork.

"The installation is designed as this waiting room where people can gather and think about the act of waiting for papers," said Srouji, who was born in Palestine, but forced to leave alongside her family during the second intifada, a major uprising by Palestinians against the Israeli occupation between 2000 and 2005.

"The Water Clock recreates the universal experience of waiting at an embassy, waiting for a visa, waiting for a permit, waiting to be admitted," Srouji added.

More specifically, the project also speaks to an experience that Srouji says has become almost universal for Palestinians since the 1948 Arab-Israeli war, when around 700,000 people – more than half of Palestine's Arab population – fled or were expelled during a period referred to as the Nakba, which means "catastrophe" in Arabic.

In the ensuing decades, the number of Palestinian refugees has grown to around six million.

"We have more Palestinians living in diaspora than we have in Palestine at the moment," Srouji told Dezeen.

"I felt like it was a really important commission for me to work on, especially now as we're seeing millions of Palestinians become refugees again 76 years later."

Around 1.9 million Palestinians – 85 per cent of Gaza's total population – have been displaced due to Israel's ongoing military operations in the blockaded territory since October.

The Water Clock is an extension of Srouji's ongoing experiments with glass since 2016. At the time, she was living in the West Bank and was introduced to a family of local glassblowers while renovating historic villages in Jaba with the Riwaq Centre for Architectural Conservation.

Together, they created a series of sculptural vessels blending traditional craft techniques and contemporary design, and a set of forgeries displayed at the V&A for last year's London Design Festival to critique the extraction of archaeological artefacts from Palestine and Syria.

"Glassblowing was originally done in Palestine, before the Roman Empire," Srouji said. "And that kind of material cultural history was really interesting to me."

However this time, due to the ongoing war in Gaza and the growing tensions in the West Bank, Srouji worked with a family-run glass workshop in China instead, recommended by one of the architect's students at the Royal College of Art.

"Shipping out of Palestine at the moment is really tricky," she explained. "And they would have had to import the glass because it's very difficult to get raw materials."

The bricks were assembled into a stepped structure to suggest an embassy waiting room and sand-blasted to create a frosted finish.

In this way, Srouji aimed to evoke the image of a water clock frozen in time and capture the feeling of time slowing down while waiting for something to happen, like "watching grass grow or paint dry".

"The embassy is a very strange space because when you finally have that interview, you can't wait to get into the building," she added. "But sitting in the waiting room or waiting at home for the call or checking your email for a file to come through, that's a very torturous experience."

This reflects the experience of many Palestinians, according to Srouji, even those who haven't fled the ongoing conflict as their freedom of movement is restricted due to Israel's occupation of the Palestinian territories.

"The process of getting a student visa for Palestinians is close to impossible," she said. "It requires $5,000 in visa fees. It requires access to the internet and access to a particular consulate in Jerusalem or a representative in the West Bank, who may or may not be there."

"Now, a lot of the consulates in Palestine and the West Bank have shut down until it's safe enough for the diplomats to come back," she added.

"So you have a whole year of people not being able to apply to university, to get scholarship grants. There are pretty massive interruptions to people being able to live abroad or even marry someone from a different place."

The Water Clock installation was created for Unfolding the Embassy, an exhibition at the Fenaa Alawwal cultural centre run by the Saudi Ministry of Culture.

The bricks used for the installation were held together using nothing but strategically placed double-sided tape in certain places so they can ultimately be reused, as Srouji hopes to turn the waiting room into a full-scale, permanent installation.

"It's essentially a proposal for a permanent sculpture for people to actually sit in," she said. "Funny that it kind of feels like the installation is waiting for its permanent home as well."

More than 36,000 Palestinians have been killed by Israel's most recent offensive in Gaza so far, which it launched following an attack by Hamas militants on 7 October 2023.

The UN's top court, the International Court of Justice (ICJ), is currently hearing a case brought by South Africa that alleges Israel's assaults amount to genocide, with a leading UN human rights expert stating there are "reasonable grounds" to believe Israel is committing genocide in Gaza.

The photography is by Abdulrahman Abdullah.

Unfolding the Embassy is on show from 16 May to 1 September at Fenaa Alawwal in Riyadh. See Dezeen Events Guide for an up-to-date list of architecture and design events taking place around the world.

Comments have been turned off on this story due to the sensitive nature of the subject matter.