"'Ideadiversity' may be at an all-time low"

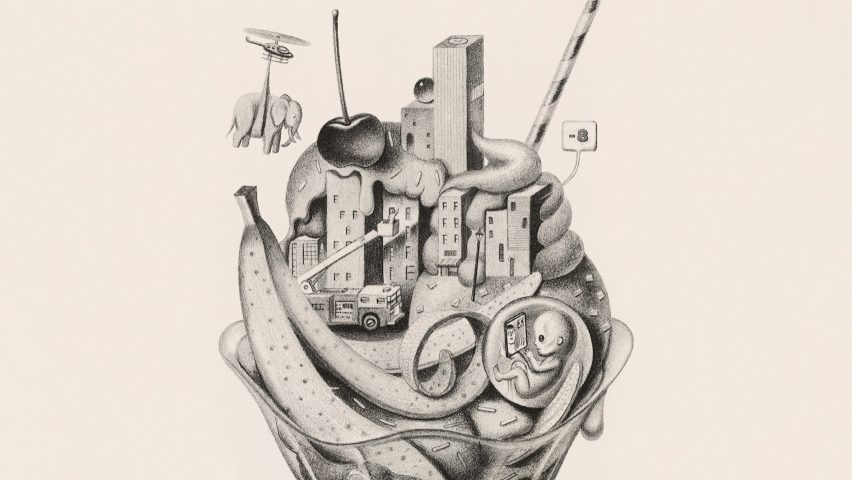

As monocultures continue to spread sameness throughout the human and natural world, Scott Doorley and Carissa Carter set out ways that designers can ensure they maintain creative diversity.

Intentional or not, the modern era has been, in many ways, a quest for sameness: globalised markets, monoculture crops, standardised protocols.

We need some sameness. It's efficient, it puts food on the table, helps people coordinate and helps ideas spread. Standards can be useful. It's convenient that within countries and regions the shape of power outlets is the same, and then glaringly annoying when you bring an electronic device overseas and need to find an adaptor.

Monoculture is popping up everywhere

But sameness also spreads trouble, and at an alarming pace. In the last 300 years, biodiversity has plummeted and we're in the middle of the sixth mass extinction of species in the last 500 million years. Cultural diversity has nosedived alongside and a language goes extinct every few weeks.

And "ideadiversity" – a new word we made up to capture flexibility of thought – may be at an all-time low as present-day politics and policies cement us into binary choices and media becomes a copy-paste perpetuation of borrowed memes and knee-jerk reactions.

As our cultures become reduced to fit into a global context, the diversity of our designs suffer too. We become stuck between runaway design – where immediate utility is valued above long-term wisdom – and a monoculture of design – where the simplicity of sameness allows you to speak to an audience of all through the broad and bland.

As much as increasing monoculture (in all ways) is an outcome of globalisation, an overarching design goal for the present and future has to be to preserve diversity while working across it. Superficially, monoculture is popping up everywhere in mimicked trends like Instagrammable faux flower photo walls and white subway tile splash guards at restaurants around the globe.

Part of this is the growing influence of algorithms in curating our experiences rather than humans with unique sensibilities and tastes. In his book Filterworld, Kyle Chayka calls these fast moving trends that are dictated by algorithms "cultural flattening".

Monocultures lack diversity, and that's the very thing we need to retain if we are to allow for design to flourish. Places that contain a lot of biodiversity tend to also be places with a lot of cultural and language diversity.

To design differently, we need to cultivate different ways to think

Cultural diversity is like biodiversity for the imagination. It promotes possibility and cultivates creativity and care. It gives our designs greater life; they become surprising, innovative and as diverse as the communities they develop within.

To design differently, we need to cultivate different ways to think. We call the nimble switching across ways of thinking and doing "shapeshifting". To shapeshift requires pushing the fringes of our disciplines and experience and exploring where they overlap with others. This breeds possibility, and we need as much possibility as we can get.

Here are some ways to shapeshift your design work.

One: shapeshift your imagination. Metaphors impact how we think and how we act. Metaphors also help shift your thinking. In fact, metaphors mould our thinking even when we're not thinking about them. For example, you may not think about the direction "up" when you talk about being in "high spirits", but it's there.

When envisioning how your next idea should work, try on a few different metaphors. It's as simple as just layering one idea on top of another to see how it feels and what it reveals, then trying something else. You can do it when you're facing a decision, trying to look at a problem in a new way, or trying to break some old habit. The key is to shift from one metaphor to another to expose what you might be missing (rather than getting hung up on any given one).

Two: mimic to shift. Analogous research (also called analogous inspiration) is the act of observing one situation to learn about another. Analogous inspiration does everything a good metaphor is supposed to – namely, changing how you see the world by highlighting some things and downplaying others.

Legend has it that the Apple Genius Bar was inspired by Apple designers chatting up concierges at fine hotels

The trick is to find one aspect of your current situation that needs some attention and think of another circumstance that could give you a different way to think about just that bit. Then go check it out.

The most famous versions of analogous inspiration tend to come from high-end product design. Legend has it that the Apple Genius Bar was inspired by Apple designers chatting up concierges at fine hotels. Analogous inspiration is a way to unlock new opportunities.

Three: the right (thinking) tool for the job. One major problem in how we create is using the wrong thinking tool at the wrong time. People shapeshift into kinds of thinking styles, but two fundamentals stand out in the ways we try to make sense of things: serial and spatial thinking.

Serial thinking is linear and relies on cause-and-effect chains like stories, arguments and logic. Spatial thinking is focused on comparison, like maps, diagrams, sketches and visual arrangements.

None is better or worse or more or less true. But sometimes we get tangled up in cause and effect when we should really be searching for similarity. Other times we're noticing dazzling patterns when we really need to tell the story of why they matter.

The way we make sense of things sets our course. As you approach anything you are trying to understand, start with what you think you need to reveal. Then try some mental shapeshifting and see what sticks.

In a world of staggering sameness and twitchy, fast moving cultural flows, tactics that leave room to morph, change and pave our own ways can help us flourish. We need all kinds of diversity – cultural diversity, biodiversity and ideadiversity – to stay resilient. This mental flexibility and interconnected diversity, rather than all-consuming monoculture or rampant disconnection, can make sure design remains a door to many possibilities.

Scott Doorley and Carissa Carter are the creative and academic directors, respectively, at the Stanford d.school. They are co-authors of Assembling Tomorrow: A Guide to Designing a Thriving Future (Ten Speed Press, 2024).

The illustration is by Armando Veve.

Dezeen In Depth

If you enjoy reading Dezeen's interviews, opinions and features, subscribe to Dezeen In Depth. Sent on the last Friday of each month, this newsletter provides a single place to read about the design and architecture stories behind the headlines.