"I was horrified at the thought of a soulless chain" - Aesop founder

Interview: recently Dezeen met up with Dennis Paphitis, founder of skincare brand Aesop. In this exclusive interview he explains why no two stores are of the same design, why he enjoys working with different architects around the world and how he believes "there's a direct correlation between interesting, captivating store spaces and customer traffic within a store" (+ slideshow).

In the interview, conducted by Dezeen editor-in-chief Marcus Fairs, Paphitis (above) explains how the brand has worked with different design teams to avoid "the kind of assault on the streetscape that retailers inflict through the ordinary course of mindless business."

"I was horrified at the thought of Aesop evolving into a soulless chain," he says. "I’ve always imagined what we do as the equivalent of a weighty, gold charm bracelet on the tanned wrist of a glamorous, well-read European woman who has travelled and collected interesting experiences. I felt and still do that it should be possible to grow in a lateral way without prostituting the essence of what the company is about."

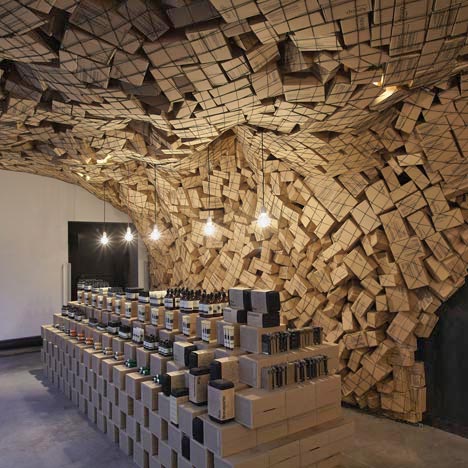

Above: Aesop at Merci, Melbourne, by March Studio

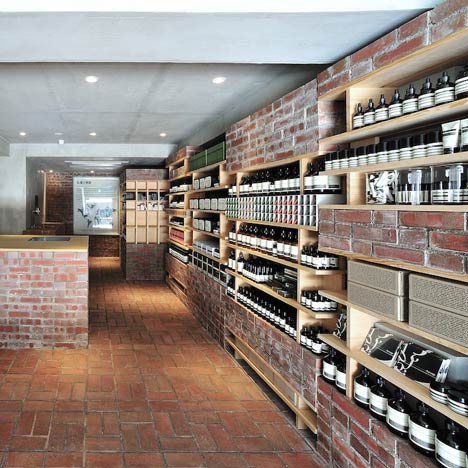

The slideshow [top of page] features several new and previously unpublished Aesop stores. See all our stories about Aesop stores.

Marcus Fairs: Tell me the story of Aesop.

Dennis Paphitis: I’m an ex-hairdresser. I guess the qualities that remain important in Aesop stores today were also important in the salon back in the days when I was cutting hair. In busy, high traffic environments a sense of calm and composure can quickly recalibrate how people feel. I attracted complicated and difficult clients, so keeping the space visually ordered and contained made it easier for me to think and work in.

Product-wise I started by adding essential oils to the commercial hair colour we were using at the time, because the smell of ammonia is quite overwhelming. Clients responded well to these less aggressive aromas. I then looked further into other ingredients and started work with a chemist on a small range of hair care products. Eventually the hair product extended to a hand and body product category and finally skin care. I started to think this could be developed into a more substantial offer if I gave myself fully to it.

So in 1996 I stepped out of the salon altogether, and spent the next few years with our first chemist setting up the foundation for a fuller product line and more serious development. All this was done without a great deal of commercial aspiration. I was simply interested in what was happening with the product and learning more about the science of manufacturing and ingredient sourcing, product shelf life: all the necessary components of developing product and trying to do something well. The idea was to use fewer, better ingredients in a smarter way.

Above: Aesop Shin-Marunouchi, Tokyo, by Torafu Architects

Marcus Fairs: Why did you decide to open your own stores?

Dennis Paphitis: We would try and explain to retailers that were retailing our product how we would like to be represented and communicated, but we didn’t have a tangible example to demonstrate this to them. It was all in our heads yet there wasn’t a physical reference. So the moment you do that and you control the smallest, most innocuous details such as temperature, lighting, music, smells, tactility, and the materiality of a space this has a very profound impact. Of course there must be a solid and serious product offer to have legitimacy, but these peripheral factors actually compliment the product line up. It was liberating and we were able to express ourselves as who we are.

Above: Aesop Saint-Honoré by March Studio

Marcus Fairs: Where was the first store?

Dennis Paphitis: The company is 25 years old however the first Aesop store proper is only 10 years old this month and we’re happy it’s still there. It’s in Melbourne, in an area called St Kilda, which I guess is a little bit like the Shoreditch or the Hackney in these parts. It felt like the appropriate area to begin in. We couldn’t find a location however there was an iconic hotel called The Prince that had a car parking ramp that was 3m wide and 25m long. They gave us this space to work with and we redirected the car park users to enter an exit from around the corner. So that was the bones of our first store.

Marcus Fairs: How many do you have now?

Dennis Paphitis: At this moment I think we have 61 stores and there are nine stores in progress; four of those are in the US, which is a huge step for us in that part of the world.

Above: Aesop Grand Central Kiosk, New York, by Tacklebox

Marcus Fairs: The design of each of your stores is different, and you’ve worked with several different architects around the world. What’s the thinking behind that?

Dennis Paphitis: After St Kilda we opened a second store in the central part of Melbourne and opened our first store in Taipei within a few months of both. So through necessity we began to work with different architects, because of the overlapping timing. For example we needed to work with a local Taiwanese architect on the first store there. And that just got me thinking about the kind of assault on the streetscape that retailers inflict through the ordinary course of mindless business, the idea that one size would so often be forced to fit all. It wasn’t so hard to respectfully consider each space individually, consider the customer, the context and to bring a little joy into the conversation.

I was horrified at the thought of Aesop evolving into a soulless chain. I’ve always imagined what we do as the equivalent of a weighty, gold charm bracelet on the tanned wrist of a glamorous, well-read European woman who has travelled and collected interesting experiences. I felt and still do that it should be possible to grow in a lateral way without prostituting the essence of what the company is about, to have the confidence to evolve yet the retain the core of what distinguishes us. It’s become politically incorrect to discuss good taste but actually this what Aesop does best. We aspire toward a certain quality, discretion and restraint in our work. These are qualities that are almost counter intuitive in a retail market desperate to cater to short attention spans and infinite choice.

Architecturally our criteria is always to try and work with what is already there and to weave ourselves into the core and fabric of the street, rather than to impose what we were doing. We didn’t ever want a standard Aesop shade of orange or green that was plastered onto stores with a nasty logo over it, but instead to look at the streetscape and try to retain and redeem existing facades that are there, and work with a local and relevant vocabulary to contextualise what we do.

There remains a core palette of ideas that we work with: we know that every store has to have sufficient display space, by product category. For example you need to be able to walk in and say to the customer, “This is where the skincare is, this is where the hair is, the body care,” etcetera. We need a counter for transactions to occur, we need water, we need back-of-house storage, some space to sit and contemplate and think about the day. So there are all these factors that don’t vary by region but the possibility of expressing them fully will vary according to space, light and budget. It’s the same product that we’re selling worldwide but it needs to fit and connect locally.

Above: Aesop Newbury Street, Boston, by William O'Brien Jr

Marcus Fairs: When did you start expanding internationally?

Dennis Paphitis: Five or six years ago we looked at where we would open the first offshore company-controlled store, because Taiwan was an arrangement with an external party there. Four of us took a trip to LA, San Francisco, London and Paris and we knew that it would be one of those four cites. We opted to set up the first stall in Paris, which was really quite absurd because none of us at that time spoke French and we were aware of the commercial bureaucracy and so forth that one deals with in France.

But actually it was quite a straightforward and invigorating process once we found a store that appealed to us in the sixth. We looked at some spaces and found a bookstore that we liked and tracked down the architect. He spoke little English but there was an immediate human connection between all of us. We worked well together, and more or less from that moment on we then started to explore the possibility of working with local architects project managing development from Melbourne.

We’ve continued on this path since with some architects that we’ve worked with many times over such as Rodney Eggleston, who is the founder of March Studio in Melbourne; we’ve just completed our twelfth project with him at Bleecker Street in New York [above]. Similarly Kerstin Thompson from KTA who we’re working on our sixth project with a new Adelaide store. We’ve completed five projects with Ciguë who are a fantastic young Paris based firm and are also beginning two London projects with them in the New Year.

My personal criteria in selecting architects for long term unions is not singularly the excellence of their work but more so their psycho-emotional state and capacity to communicate, function under pressure and ultimately deliver the goods with minimal trauma. There are some very impressive characters out there, this year we’ve begun three projects with NADAAA in Boston who are perhaps the most professional and sophisticated firm we’ve worked with.

Marcus Fairs: You tend to have clusters of stories in cities like London and Paris, rather than one store in every city. Why is that?

Dennis Paphitis: The thing with us is we like to go deep rather than wide, so we can’t set up a store in London then just open another one in Barcelona and in Glasgow because it seems like a good idea. We need to do a series of interconnected stores in London or whichever the chosen city is because we need the back office support structure to make it all work and hang together well. Less spread, more depth of presence with a strong and switched on infrastructure to support this.

Marcus Fairs: What influence does interior design have on sales and the performance of the shop?

Dennis Paphitis: There’s a direct correlation between interesting, captivating store spaces and customer traffic and interest within a store. I’m personally more comfortable with under-designed looking design, if that makes sense, or design that dissolves and recedes rather than screams ‘look how clever I am’. It’s not singularly the design but also a whole series of seemingly miniscule decisions and very fine calibrations that converge together to make space captivating and comfortable to be in.

Above: Aesop at I.T Hysan One, Hong Kong by Cheungvogl

Marcus Fairs: How do you choose your architects?

Dennis Paphitis: We like to take them green but not too green; they need to have a little bit of blood on their hands. The minimum criterion is five years post-graduate working experience unless they’re extraordinarily talented and there’s some compelling reason to consider them. But if they’re 15 years into their professional journey we need to check that they’re not having a mid-life crisis or whatever it is that might implode or distract them during the process. It’s a fine line.

We sit down and share coffee and meals and try and understand their motivations. Often we are the ones seeking them out, we will see something they’ve done, hear about a talent graduate, discover some long ago project that captivates us. And then we present what we need to achieve with them and give the scope to interpret this whilst at the same time ensuring that there are sufficient shelves to store our product and a space for our staff in the back room to have lunch, a point of sale, and basins because we need water in every store, and a provision to have music, and all of the practical details that make a retail space functional and successful.

Above: Aesop Ginza, Tokyo, by Schemata Architecture Office

Marcus Fairs: How involved do you get in the design of the stores?

Dennis Paphitis: Once an architect has my allegiance and loyalty they’re pretty much given carte blanche but they do need to earn it and they need to be respectful to keep it. With the guys in Paris, Ciguë, who are almost like some sort of contemporary experiment in architectural socialism, they’re extraordinarily hard working, committed and diligent, earnest and talented. Nothing with them ever runs on time, nothing runs to budget, nothing emerges in the way that you expect it to, but they pour their hearts into every job, see it through and remain responsible for the upkeep with an almost Victorian sense of propriety and dignity. I like this sense of responsibility.

We had hand-blown glass taps made by them for the Islington store, which exploded! But they will hand-blow them again and we’ve all learnt from that. It never regresses into a vulgar conversation around blame and who is responsible.

Conversely there are arrangements that we have in other parts of the world that are much more structured and sober and these are the ones that deliver at 10am on Monday 13th because that’s what’s been agreed. The work is still of a very high standard. I’m not sure if these have the same poetic capacity to arouse and to captivate, but it’s work that will certainly do its job and fulfil the brief. Personally it’s that little extra manic commitment and diligence that motivates and drives me so I enjoy this with people I work with.

Above: Aesop Le Marais, Paris, by Ciguë

Marcus Fairs: Is your approach to hiring architects changing as the company grows?

Dennis Paphitis: What I’ve proposed is that we standardised the relationship that we have with some architects and make it a ‘marriage’ in specific regions. I’ve always worked on a “What if I get hit by a truck?” theory, so I am no longer involved in the commercial aspects of the company. My role is now more an arm’s length creative provocateur, just to kind of stir the pot a bit where I sense the design decisions being made are perhaps too safe and less energised than they might be. The truth is that many of my colleagues are far more visionary and driven than I am and have the capacity to develop and further explore the company’s next chapters.

Above: Aesop store in Singapore by March Studio

Marcus Fairs: Which store is your favourite?

Dennis Paphitis: I think the current personal favourite is always the most recent store because it’s like a new lover or something similarly engrossing. You become immersed in the moment but then they become like children and you could never admit to favouring one over the other.

We’ve just opened a fourth store in Paris in Rue Tiquetonne [above] and a sixth in London in Islington [below]. I think both of these are particularly interesting, they feel like a logical evolution of what we’ve explored with Ciguë to date. Earlier in the year we opened a little gem of a store in Collins Street, Melbourne designed by our creative team with Kerstin Thompson. The thinking behind that store was very much around speaking with men, because the location is in the banking end of town, there are lots of institutional clubs for men, bankers and the rest of it. The material references for this space are all quite sturdy, traditional yet at the same time a little subversive to an educated eye.

Then we opened Geneva [see slideshow] three months ago. This one was intended to evoke more a decadent living room of maybe a central European or Middle Eastern undercover agent with an apartment in Geneva. There is extraordinary copper detailing and stuccoed plaster, quite beautiful matt, saturated skin toned walls, so that was also an interesting one.

And we also opened a second store in Zurich [see slideshow]. That was constructed largely out of cork. I’ve always been interested in cork because of the tactility and the acoustic qualities that it has. It’s a very small store though it has high visual impact and it’s been well received. Then Islington, which opened about four months or so ago. The reference point here was nurseries and seedling trays that you could slide open and close. Ciguë used a lot of plants, and since opening, the plants have quadrupled in size and grown all over the walls and products so this idea of a store never being quite finished or static is very much our thing.

We’re working with an interesting lighting firm in Beirut called .PSLAB. They’ve resolved a long-standing Aesop lighting dilemma, because our stores are generally quite under-lit by standard retail measures and they’ve managed to gently increase the lighting levels a little yet still keep it all soft and human and more living room like.

Above: Épatant, Melbourne by Dennis Paphitis and Lock Smeeton

Marcus Fairs: You’ve set up a new retail concept for men. Tell me about that.

Dennis Paphitis: Épatant [above] is a separate non-Aesop project that I’m working on for a day a week. It’s intended as a kind of mental palette cleanser for me; a distraction that I can amuse myself with. I have a business partner on this project and we’ve been speaking-thinking for the last couple of years about the way men behave in a retail context, what switches them on, what engages them and what just closes them down.

It’s really just an edit of product that we like and already use and felt deserved a base to be presented from. Épatant means “dapper gent” in French and the idea was that we would have product that address all categories of a man’s life from birth until death, without necessarily touching fashion. Fashion is not something we know, and with sizes and seasons it just becomes too complicated and kind of tedious.

So there’s a website and a physical store and the idea is you can shop by brand and you can shop by category: fitness, wellbeing, personal grooming, car, office, outdoors, and so forth. Or you can shop by milestone, if you’re buying a gift for someone; birth, graduation, divorce, retirement, whatever it may be.

We share the space with some Japanese friends who have developed a food offer, thinking what does a guy want to eat for lunch? The options are quite limited in terms of food. It’s an interesting project. We also represent Aesop there because in the grooming category it was the only logical option. I generally spend four days a week working on Aesop and one day on Épatant, and I think it’s been constructive. One project fuels the other and keeps it interesting for me. It’s the first non-Aesop workplace thought I’ve had in twenty five years and I’m still trying to figure out what it all means.