Property prices are "castrating the whole notion of city life"

News: the rising cost of property in city centres is causing the "biggest crisis" facing architects and urbanists, according to critic Joseph Rykwert, the recipient of this year's RIBA Royal Gold Medal (+ interview).

Speaking to Dezeen the day before being awarded British architecture's most prestigious award, the 87 year-old spoke with concern that the increasing cost of city centre property would make the diversity that makes cities thrive impossible.

"What's happening is that - this is common knowledge - the price of property in city centres is making it impossible, particularly in the big cities, for any kind of social mix to take place. It's castrating the whole notion of city life," he said.

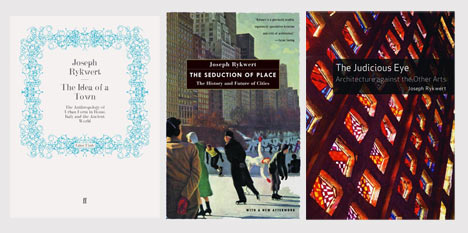

Rykwert is known for his large body of work on cities including his seminal 1963 book The Idea of a Town, which his RIBA Gold Medal citation called "the pivotal text on understanding why and how cities were and can be formed". His other books include The Necessity of Artifice and The Seduction of Place.

Though the life of cities were one of his early topics, the rise of cities with over 20 million occupants holds little excitement for Rykwert. "They are not very happy places are they? Extremes of inequality are underlined in the way those kind of cities are built and extremes of inequality always tend to show up in political movements."

The other major challenge facing architecture is climatic, said Rykwert. "We have an energy crisis and … if we go on building large, glass-faced, air-conditioned buildings we will exacerbate the situation. And this is what’s we are doing".

Rykwert said architects can - and should - try to make modest improvements wherever they can, and understand the impact they can have. "It's very important that architects understand their own power and that what they do is something which is of enormous impact to society. Not that I believe that architecture influences social behaviour directly, but it certainly does so indirectly."

The critic believes that contemporary architects need to take a more intelligent engagement with the past. "At the moment architects tend to ignore the past. Yet the past is all we know. We don't know the future. The way in which the past and the present mesh is something I find a bit lacking in current architecture discourse," he said.

Rykwert was born in Poland in 1926 and moved to London in 1939. He is Paul Philippe Cret Professor of Architecture Emeritus at the University of Pennsylvania and has taught at the University of Cambridge, Princeton, the Cooper Union, New York, Harvard Graduate School of Design and the University of Sydney.

The RIBA Royal Gold Medal is the institution's highest honour, given to a person or group in recognition of a lifetime's work and for significant influence "either directly or indirectly on the advancement of architecture." The Queen personally approves each recipient, and recent winners have included architects David Chipperfield, Herman Hertzberger and Peter Zumthor.

Other architectural writers and critics who have won the medal include Nikolaus Pevsner and Colin Rowe.

Announcing the award last September, RIBA described Rykwert as "a world-leading authority on the history of art and architecture" whose "groundbreaking ideas and work have had a major impact on the thinking of architects and designers since the 1960s and continue to do so to this day".

Here's a full transcript of the interview:

James Pallister: Congratulations on being awarded the Royal Gold Medal.

Joseph Rykwert: It wasn't wholly expected I must say!

James Pallister: I suppose you wouldn't expect to get a gong from the profession you criticise?

Joseph Rykwert: Exactly. Though I'm not an adversarial critic.

James Pallister: What's missing from architectural discourse today?

Joseph Rykwert: Well a sense of power. Architects don't have a sense – perhaps power is the wrong word – they don’t always have the sense of the authority they should have.

I think it's very important that architects understand their own power as it were and that they understand what they do is actually something which is of enormous impact to society. Not that I believe that architecture influences social behavior directly, but it certainly does so indirectly.

James Pallister: For you, as a critic and a historian, is it important to engage the public in the architectural debate or is it ok to solely engage the architectural profession in debate?

Joseph Rykwert: Well the trouble is that very few people outside those who have actually been trained professionally have much of an understanding of architecture. One of the essential skills in judging a building before it is built is the ability to read plans. I really am sometimes quite horrified at how few people can read plans.

James Pallister: Do you think critics are still relevant today, given the power of the internet, and the globalization of architectural media?

Joseph Rykwert: Come on! We are all critics. We are all critics all the time. That's what criticism is about. The Greeks used the word to signify winnowing. You have a winnow net, you throw things up and the wheat comes down and the chaff flies away. And that's what you hope to do when you are a critic: separate the grain from the chaff.

James Pallister: Was there any particular artist or architect who made a big impact upon you in your early career?

Joseph Rykwert: Well the dominant architect of my time was Le Corbusier. No doubt. He was obviously the greatest architect of his generation. He was also the most insistent publicist – some people would say self-publicist. You could look at his buildings, and you could read his writings. This is not true of Walter Groupius or of Alvar Aalto, certainly not true of Mies van Der Rohe. Mies was very laconic, as I'm sure you know. Not only laconic but also gnomic.

James Pallister: How hopeful are you for the future of architecture?

Joseph Rykwert: Well as always we are at a critical moment. Architecture is permanently in crisis. The crisis now is as much financial as technical. What's happening is that – this is common knowledge – the price of property in city centres is making it impossible, particularly in the big cities, for any kind of social mix to take place. It's, as it were, castrating the whole notion of city life. And I have no idea what will happen as a result, but something must. I probably won't see the consequences but it's something, which is bound to have a long-term effect.

James Pallister: Is that the biggest issue facing architecture?

Joseph Rykwert: Well it's certainly the biggest issue facing urban planning.

James Pallister: You've seen the rise and fall of idealistic modernism and the emergence of sustainability as an interest of many: what's your definition of a sustainable city?

Joseph Rykwert: I think it's a word that's up for grabs, isn't it.

The fact is that we have an energy crisis. In this country we don't need to underline it, we've just had the floods, which may be or may not be a seasonal phenomenon independent of global warming but certainly the extreme weather phenomena all over he world, including heat waves in Australia and south-east Asia, are almost certainly related to it.

If that makes parts of Equatorial Africa and Equatorial America uninhabitable it will mean the population will shift, either north or south – probably more north than south. This will create a population crisis. It's already, in a minor way, in place in the northern shores of the Mediterranean. They can't cope with the influx of refugees. I've no idea what will happen as a result of that and I don't wish to prophesy because it's a risky business. But it is a permanent crisis, which doesn't seem to be going away.

James Pallister: What is architecture's role in this?

Joseph Rykwert: Well if we go on building large, glass-faced, air-conditioned buildings we will exacerbate the situation. And this is what's we are doing, so it's anyone's guess what will happen.

James Pallister: Do architects have an ethical duty here?

Joseph Rykwert: I would have thought they did. I'm certainly in no position to dictate it. But as a critic you are bound to note that sort of thing.

James Pallister: In general do you think that architects should make the world a better place?

Joseph Rykwert: That's what it's about! If it's not about that it's not about anything.

James Pallister: Some people say that bad things happen when architects think they can change the world…

Joseph Rykwert: I didn't say change the world. I said make it a better place. The world is changing anyway without architects. Maybe it could do with a bit of help every now and again.

James Pallister: Is there anything missing from architectural discourse today?

Joseph Rykwert: What I do miss is a sense or consciousness of the past. Past achievement is not something that should weigh heavily on architects but something that should be part of –as it were – the fertilising ground on which they grow.

Architects tend to at the moment ignore the past. Yet the past is all we know. We don't know the future. I'm not a great believer in reaching out beyond what you can learn both from the past and the present. The way in which the past and the present mesh is something I find a bit lacking in current architecture discourse. Which is why historicism is really a danger. There are people who see the past as a kind of quarry (which is sterile, of course) instead of thinking it as the kind of ground and manure and fertilising background…

James Pallister: Who are the most interesting architects working today?

Joseph Rykwert: Well the architect I've worked most closely with is David Chipperfield. There are older figures. Richard Meier in America has also done some wonderful buildings. Frank Gehry is another one who has done interesting and fascinating work.

James Pallister: Does the growth of cities with over 20 million inhabitants in places like China excite you, as a writer on the life of cities?

Joseph Rykwert: They are not very happy places though are they? Extremes of inequality are underlined in the way those kind of cities are built and extremes of inequality always tend to show up in political movements. However that will work out I've no idea.

James Pallister: Why do you think architectural theory matters?

Joseph Rykwert: Well at the moment there's much too much of it! It only really matters if it effects practice. As an independent discipline, I think it's really rather boring.

James Pallister: What do you mean there's much too much of it?

Joseph Rykwert: Well the amount of interminable books published on architectural theory! I don't have to list them. Just go down to the RIBA Boookshop and look at the shelves. Theoreticians who don't look at real buildings are of no interest to me.

James Pallister: How do you think that critics can make architecture relevant to the public today?

Joseph Rykwert: Well only if the public reads them. So they have to reach out to the public. They have to be accessible. They have to write as if they weren't some sort of superior being, but as if they were like everyone else.