Brutalist buildings: Pilgrimage Church, Neviges by Gottfried Böhm

Brutalism: one of the most revered religious buildings of the Brutalist period is Gottfried Böhm's Church of the Pilgrimage in Neviges, the crystalline structure that abandoned traditional Catholic architecture in favour of sharp angles and rough concrete (+ slideshow).

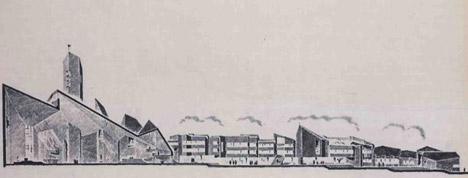

Church of the Pilgrimage, also known as Neviges Mariendom, is a colossal concrete form that rises above the rooftops of the medieval German town. It announces the destination of a historical pilgrimage that once attracted hundreds of thousands of visitors each year.

Designed in 1963 and consecrated in 1968, the structure was one of dozens of churches conceived by the German Pritzker Prize winner, but is widely considered to be his greatest work and has been associated with various artistic movements.

"Brutalism, as Pevsner somewhat irritably observed, was Expressionism revived, Neo-Expressionism. This is perhaps nowhere more apparent than in the work of the virtuoso Gottfried Böhm, most evidently in his Mariendom at Neviges," said critic Jonathan Meades.

"It is a building of thrilling geometries whose exterior borrows from geological formations, penitents' hoods and forms that might be described as anthropomorphic, had humankind obliged by being a bit more chiselled," he told Dezeen.

Böhm was one of 17 architects invited to design an all-new church for the hillside site where, in the 17th century, a friar had delivered a rendering of the Virgin Mary to a small chapel.

Some years later the prince bishop of the region claimed to have been miraculously cured from illness by the image and the pilgrimage was created.

Böhm chose to defy the competition guideline to put the church's entrance near the train station, instead opting to create a procession across the site.

He proposed a building on the site's highest peak – the only design that didn't involve flattening the landscape – so that pilgrims would need to climb up to it.

Although originally thought by judges to be too exaggerated and manneristic, the architect's vision was eventually selected.

The resulting structure became the second largest church north of the Alps – with seating for 800 and standing room for 2,200 – yet was free of any traditional religious symbolism. The angular roofline is most commonly compared with the shape of a tent.

"Time and again, the architectural forms of the pilgrimage church in Neviges have been interpreted as a tent," wrote Karl Kiem in his 2006 essay The Multi-layered Concrete Rock.

"This might appear to symbolise the pilgrim's wanderings and consequently was considered to be the adequate expression of a pilgrimage church."

Concrete surfaces were cast against wooden boards to give them the rough texture typical of Brutalist buildings. Some areas were then sand blasted, creating a grainy surface.

"Although an eccentric object on its site, its artificial nature does not conflict with the surrounding structures. The architectural design of the building is clearly linked to its time but it is also deeply rooted in the tradition of the pilgrimage church," added Kiem.

The approach sequence begins at the base of a grand staircase. From here, visitors walk up past a parade of circular bays raised up on round columns, designed to accommodate pilgrims staying overnight.

A small courtyard leads into the entrance – a deliberately confined space that emphasises the diminutive scale of the hall beyond.

Brickwork paving and street lamps continue inside the building to give the interior the feeling of a covered public square. Böhm also added his own custom details, from limited edition chairs to bespoke stained glass windows and door handles.

Three-storey galleries line one side of the space, while the other provides access to two chapels. Skylights and high-level windows bring narrow beams of light in from above.

Like many post-war buildings, maintenance has become one of the building's main failings. Originally intended for summer use only, the concrete structure did not have suitable insulation to keep the heat in during the winter months.

Local residents introduced heating, which disrupted the thermal balance. The top of the structure was also coated with a paint sealant, which has created a visual separation between the walls and roof.

Böhm, who still lives in Cologne, was awarded the Pritzker Prize in 1986. The architect has stayed involved with the upkeep of the building and continues to visit regularly.