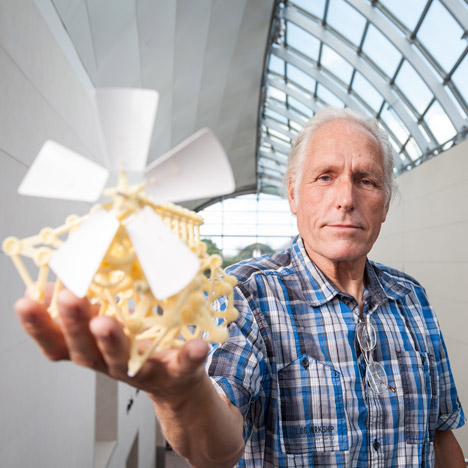

"I try to make new forms of life," says Strandbeests creator Theo Jansen

Interview: Dutch sculptor Theo Jansen has spent the last 24 years developing a series of wind-powered machines called Strandbeests that he describes as "a new species on Earth". Dezeen caught up with him on Miami Beach last week, where he explained how his creations are now evolving without his help (+ movie).

"I try to make new forms of life which live on beaches," said the Dutch artist. "And they don't have to eat because they get their energy from the wind."

He explained how the idea first came to him when writing a newspaper column exploring ways to prevent erosion of the sand dunes in Holland.

"I raised the idea that there could be skeletons on the beach, which were driven by the wind, and they would gather sand to build up the dunes," Jansen said. "So this was in fact a way to save Holland from drowning in the North Sea, which is rising."

He later started building such machines himself using plastic tubing from DIY stores, but quickly forgot about the original purpose of the "beests" and instead became fascinated by the possibility of creating a new species of man-made animal.

"Surviving is the purpose," said Jansen, 66. "These animals, they found a way – in fact a very clever way – to reproduce. And they did that behind my back."

Jansen was in Miami Beach for the exhibition Strandbeest: The Dream Machines of Theo Jansen, which was presented by luxury watch brand Audemars Piguet and the Peabody Essex Museum during the Art Basel and Design Miami fairs.

The movie at the top of this article is by Alexander Schlichter, whose documentary about Theo Jansen and his Strandbeests is available to download here.

Here is a transcript of the interview:

Marcus Fairs: Tell us who you are and what you're doing here on Miami Beach.

Theo Jansen: Well, I'm Theo Jansen and I'm a kinetic sculptor. And I’m showing my work for the first time in a group of, sort of, animals. I try to make new forms of life which live on beaches. And they don't have to eat because they get their energy from the wind. And during the 24 years that I've been working on these beasts, there has been a sort of evolution. They have become better and better at surviving storms on the beach. I hope to spend the next 20 years evolving these animals and making them better. When I leave this planet, these animals will be a new species on Earth.

Marcus Fairs: Tell us the story of how you first came up with the idea of building Strandbeests.

Theo Jansen: I used to be a writer. I wrote columns in a newspaper, in the science section. It was a strange look at the world. And in one column I raised the idea that there could be skeletons on the beach, which were driven by the wind, and they would gather sand to build up the dunes. So this was in fact a way to save Holland from drowning in the North Sea, which is rising.

So after publishing this column, I didn't do anything for a long time. Then came this day that I passed the tool shop where they sell this kind of [plastic] tube – because we use these kinds of tubes in Holland as ducts for cables in houses. So I bought some of these tubes, and after that I played for an afternoon with these tubes. And by the end of that afternoon I decided to spend one year on the tubes. And I also had the illusion that I would be finished after a year. Of course that was not true. It was maybe a naive view of the world because I'm still attracted to the tubes and still busy realising this plan.

Marcus Fairs: And now you build Strandbeests full time?

Theo Jansen: Yes.

Marcus Fairs: How would you describe your relationship with the beests? Are you their inventor, creator or curator?

Theo Jansen: Well, you could say that the beests and I are living in symbiosis because the beests cannot do without me, and I cannot do without the beests anymore. So there is a sort of cooperation where we both get benefits from each other.

Marcus Fairs: Do the beests still exist to push sand onto the dunes, or have they become something else?

Theo Jansen: I have forgotten about that because during the process I got so much more interested in the history of evolution that I forgot all about saving the country because this dream, at that moment, was more important for me.

Marcus Fairs: You talk about evolution. Are they evolving towards some kind of particular purpose? Or is the purpose of it just so that they can survive?

Theo Jansen: Surviving is the purpose. All living things are living for reproduction. What we find in nature is something which will reproduce itself. These animals, they found a way – in fact a very clever way – to reproduce. And they did that behind my back.

Marcus Fairs: How do they do that?

Theo Jansen: In the middle the beests have this sort of spine. The spine makes a circular movement, and that circular movement is transformed by a number of tubes to a walking movement by the shoe which is under there. And this particular movement is to do with the proportion of the lengths of the tubes which are in-between the spine and the shoe. The proportions are based on thirteen numbers. And this particular proportion takes care that the animal stays on the same level while walking.

And that's the special thing of Strandbeests, because normal animals always toss up and down as they walk, but the Strandbeests stay on the same level. You could see this proportion of thirteen numbers as the DNA code of the Strandbeests.

I published this DNA code on my website. Since then, thousands of students around the world are building Strandbeests. And all these students, they think they're having a good time. They think they're happy. But in fact they're being used for Strandbeest reproduction! So the Strandbeests abuse students for their reproduction.

And there's a new kind of Strandbeest that doesn’t survive on beaches. They have found a protection against wind. They can survive in student rooms and bookshelves. This is in fact a better environment than on the beach. Now in all corners of the world you see appearing these small beests, and this Strandbeest reproduction went into an acceleration a few years ago. Two guys came to my studio, and they put something on my table: a walking Strandbeest. And this Strandbeest turned out not to be assembled but to be born. It was born in a 3D printer. Nowadays you have special 3D printers which can make moving parts and moving things which you don't have to assemble. They come born in one piece. You can imagine what happened next. You can put a series of 0s and 1s on the internet – the DNA code – and everywhere around the world you can print out these beests.

And that's what's happening now, which is totally out of control. And there are now imitations on the internet which run better than my DNA code. So there's a real evolution going on which you cannot stop any more. And we all think that we are doing it but, in fact, the Strandbeests hypnotise people to do this.

Marcus Fairs: It's like cats. Cats were wild animals that became domesticated. Today we think of a cat as a pet but actually the cat has other ideas.

Theo Jansen: The cat behaves in a way that we like and that's why we breed them and we feed them. It's the same kind of evolution.

Marcus Fairs: And this DNA code, this mechanism, did you invent that or did it already exist?

Theo Jansen: I invented it. In 1990 I wrote a genetic algorithm on a computer to define these certain lengths. And this is the big secret. The way of walking was done on that computer.

Marcus Fairs: So it wasn't trial and error? You didn't do thousands and thousands of iterations?

Theo Jansen: Well yes, because the mathematics of the first leg I made was very complicated. It had two cranks at ninety degrees connected in a certain way to two limbs, which went up and down. That was the first limb. Then I had a third limb to lift up and put down on the ground to give forward movement.

This first beest could only move its legs when it was lying on its back. It just couldn't stand on its feet. But I learned a lot from that. Then one night in 1991 I couldn't sleep, so I brought the crankshaft closer to the leg and made it a lot simpler. That same night I realised I had to write a new algorithm in the computer to define the lengths of the tubes.

Marcus Fairs: Do you know about the Mine Kafon? It’s a concept for a wind-blown device to clear land mines.

Theo Jansen: Oh yeah! I know it, yeah! By Massoud Hassani?

Marcus Fairs: It's to destroy mines in Afghanistan.

Theo Jansen: That's Massoud, yeah. I know him. He's been several times to my studio.

Marcus Fairs: And what do you think of that project? It has been quite controversial.

Theo Jansen: Well, of course, this is a very good idea, but I think practically he has a lot of problems, yeah. I wonder if it's really going to be effective. Because he thinks that it's a low investment but you have to have very many to have an effect, I think. Of course, I'm an amateur because I don't have any experience in Afghanistan minefields.

Marcus Fairs: Maybe your beests could do the job better?

Theo Jansen: No, no. In fact because my beests only like very flat surfaces. That's why they only survive on the wet part of the beach – or they could live on ice lakes. But they don't like uneven surfaces. They are not good for Mars, no!

Marcus Fairs: Do you have any plans to develop beests to live in different habitats, or serve some kind of useful function such as clearing landmines? Or are you happy with this species you've created?

Theo Jansen: Well, I have to be happy with what is happening now because this already cost me also so much time and effort. If I want to develop the Desert Beest or the Bush Beest or whatever then I'd need a few more lives to do all this! I have only twenty years left, so I'm very much in a hurry to create the autonomous beach animal that's designed for the beach where I was born, and where I'm probably going to die as well. And that particular beast will have to survive over there.

Marcus Fairs: What's the name of that beach?

Theo Jansen: It's called Theo Jansen Beach. You can find it on Google Maps.