Galleries around the world are finally "starting to take digital art seriously"

Movie: in this film produced by Dezeen for the British Council, leading artists and curators discuss the increasing significance of digital art and the new opportunities open to artists working "in a digital age."

"Digital art has been around since the 1950s," claims writer and curator Conrad Bodman. "But not many museums and galleries have focused on it as a serious subject matter."

"In the last ten years that's really changed. Many venues around the world are now having a serious look at this area and the artists that are working in it."

In 2014, Bodman curated Digital Revolution, an exhibition at the Barbican in London, which explored how digital technology is transforming the arts.

"There have been recent shows [about digital art] at the V&A, the Tate and the big exhibition at the Barbican and I think there will be many more to come," he says.

Bodman picks out two interactive pieces of art as highlights from the Digital Revolution exhibition.

The Treachery of Sanctuary by Chris Milk consists of three 30-foot high screens, which transform visitors' shadows in different ways using a Microsoft Kinect.

At the other end of the scale, Pinokio by Adam Ben-Dror and Shanshan Zhou is a desk lamp, which uses camera and Arduino computer-based technology to interact with people as if it was a living creature.

"On one level it's a design item," Bodman says. "But I think it's indicating that objects can have real character and can engage us in new and exciting ways. For me, that's what makes it art."

Other artists, such as duo Jon Thomson and Alison Craighead, are experimenting with digital data as a medium in and of itself.

"We look very much at the materiality of data and what that might mean for us as artists," says Thomson.

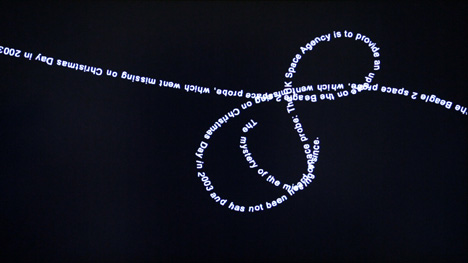

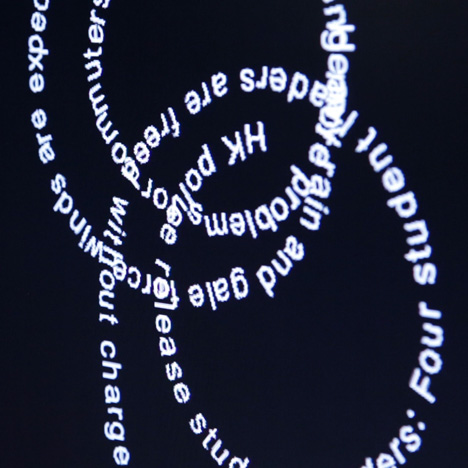

One of Thomson and Craighead's early digital works is called Decorative Newsfeeds, which pulls news headlines from RSS feeds on the internet and manipulates them into patterns on screen.

"We thought, if data is our material, can we draw with it?" says Craighead. "This is us trying to draw with a live news headline."

Thomson adds: "News presents itself as a form of truth and if we just cross two or three headlines together perhaps it draws your attention to how what is purported to be fact may actually be manipulated."

Thomson believes that their choice of medium does not make their work different from any other artist.

"It's very easy to describe us as 'digital artists'," he says. "But we're just artists that work within the contemporary art context [with] all of the kinds of concerns that we share with artists that might be working sculpturally or might be working with paint, or any kind of material."

Artist and curator Margot Bowman agrees with this sentiment. "Digital art is just art made in a digital age," she says.

Together with Sean Frank and Jolyon Varley, Bowman is co-founder of 15 Folds, a digital art gallery that specialises in animated GIF art.

"People literally all over the world are making work like this, so it feels amazing to be able to give people's work a home that it's totally deserving of," Bowman says.

Each month 15 Folds showcases work by 15 artists based around a particular theme.

"When we first started the project we would go out and approach artists, people who's work we really liked," Bowman explains. "But increasingly we have people approach us."

Other popular websites showcasing digital art include Vice and Intel's The Creators Project and The Space, an online gallery that commissions new work by digital artists.

Sean Frank of 15 Folds believes it is now possible for young artists to make a name for themselves without being dependent on brick-and-mortar galleries.

"You can set up your own blog in seconds and start posting your own work," he says. "You gain followers and people see your work. But it's also about taking an interest in other people's work and building this sense of community, which I think is really important."

Bodman agrees that this is one of the great advantages of digital art.

"That whole notion of a struggling artist in the studio waiting for the next opportunity in a gallery is no more," he claims. "You can really be out there practising amongst a very wide community and getting an instant response, which is why digital is so exciting I think."

This movie was produced by Dezeen for the British Council. The music is by UK producer 800xL.

Additional footage was provided by Barbican, Chris Milk, Tate, Thomson & Craighead, Troika and Adam Ben-Dror. Special thanks to BFI and Chisenhale Gallery.