Tiny devices replicate human organs to provide an alternative drug-testing method

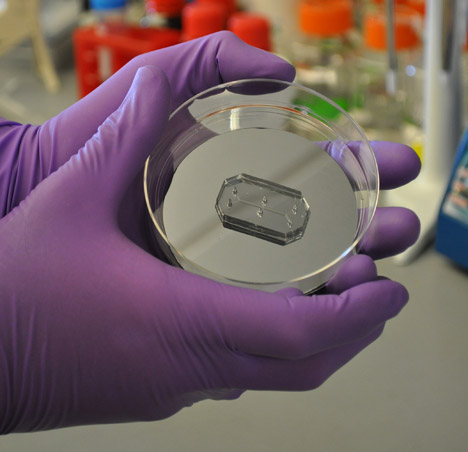

Scientists at Harvard University have developed a microchip that can be lined with human cells to mimic the complex tissue structures of human organs.

The tiny devices, known as Organs-on-Chips, were designed by members of the Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering and are nominated in the product category for the Design Museum's 2015 Design of the Year award.

The chips are designed to emulate the functions of various human organs, and can be used for purposes including drugs and cosmetics testing, as well as for the treatment of infections and inherited diseases.

The first micro-device, a Lung-on-a-Chip, was developed in 2010 by the institute's founding director Donald Ingber and former Wyss Technology development fellow Dan Dongeun. The team has since developed additional chips to represent other human organs including the gut, kidney and liver.

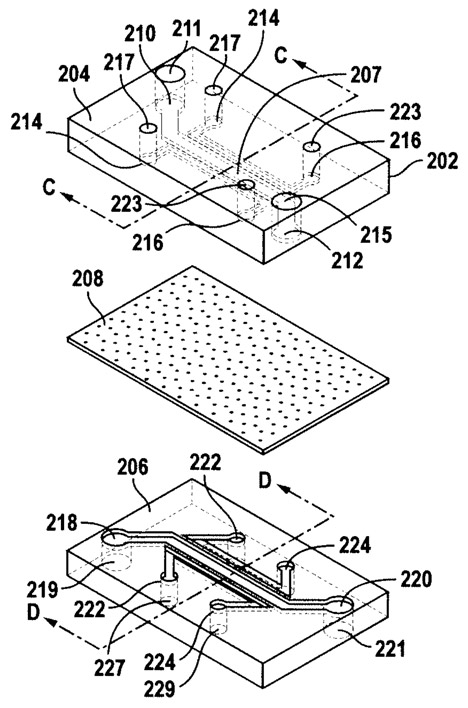

The devices are crafted using multi-layer photolithography – a fabrication process adapted from the computer chip industry that allows microscopic channels to be moulded within a transparent polymer.

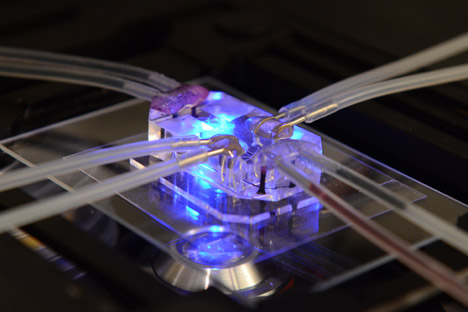

These hollow channels can be lined with living cells from different types of tissues and fed with fluids and liquid blood substitutes, in a process that mimics the flow of blood and air movement in our internal organs.

In the first development of the micro-chip organs, layers of tissue from the lining of the lung and the surrounding blood vessels were placed across a porous boundary inside of the device.

Researchers then introduced bacteria into one side of the chip while simultaneously flowing white blood cells through a channel on the other side, resulting in an immune response that killed the bacteria.

The success of this experiment allowed scientists at the Wyss Institute to observe how biology works in the context of living, physical cells.

"A crucial part of the design of human Organs–on–Chips is their ability to mechanically mirror the dynamic physical microenvironment found in living organs," said Ingber. "Including flowing fluids and tissue distortion similar to that seen during breathing and peristalsis, which enables them to replicate whole-organ functions."

This process means the chips can be used to test the safety and efficiency of new drugs, offering a more reliable and affordable alternative to existing methods.

"The drug development process is currently very costly and time consuming," explained Ingber. "Even drugs that are successful in animal studies often fail in clinical trials in humans."

The team have recently created a flowing medium to connect the vascular channels of different Organs-on-Chips together, mimicking the flow of blood from one organ to another.

"This allows scientists to replicate a human 'body' on chips," added the Wyss Institute, "and to see how drugs or chemicals impact each organ as the body metabolises compounds."

The Organs-on-Chips have been recognised in this year's Design of the Year awards shortlist for their potential to deliver advanced health and pharmaceutical care. Other nominations in the product category include a safety-conscious LED bike light and a mobile toilet designed to improve sanitary conditions in areas of extreme poverty.