Inequality still a serious issue in US architecture, say female architects

Women are being driven out or held back from careers in architecture by long hours, childcare, unequal pay and the likelihood of being passed over for promotion, according to a major new survey by the American Institute of Architects released to coincide with International Women's Day.

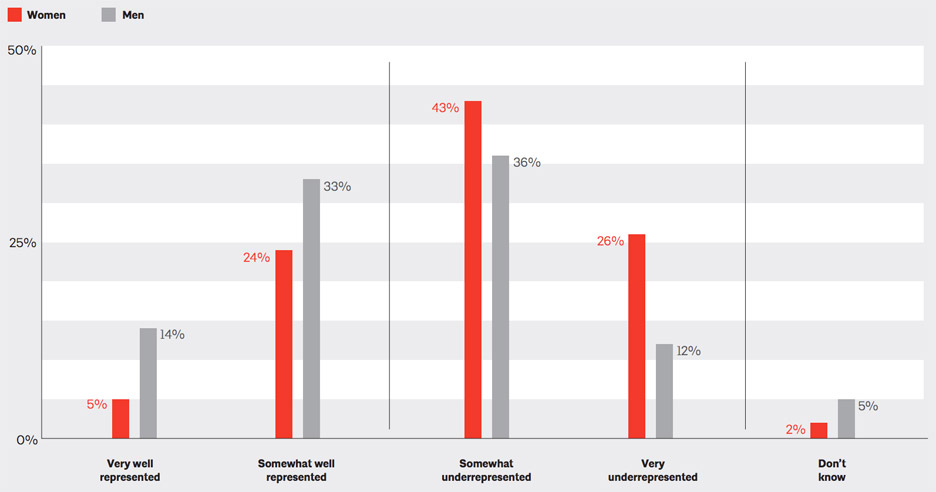

More than 70 per cent of female architects and architecture students in the US feel that women are still underrepresented in the profession, according to the American Institute of Architects' (AIA) Diversity in the Profession of Architecture survey.

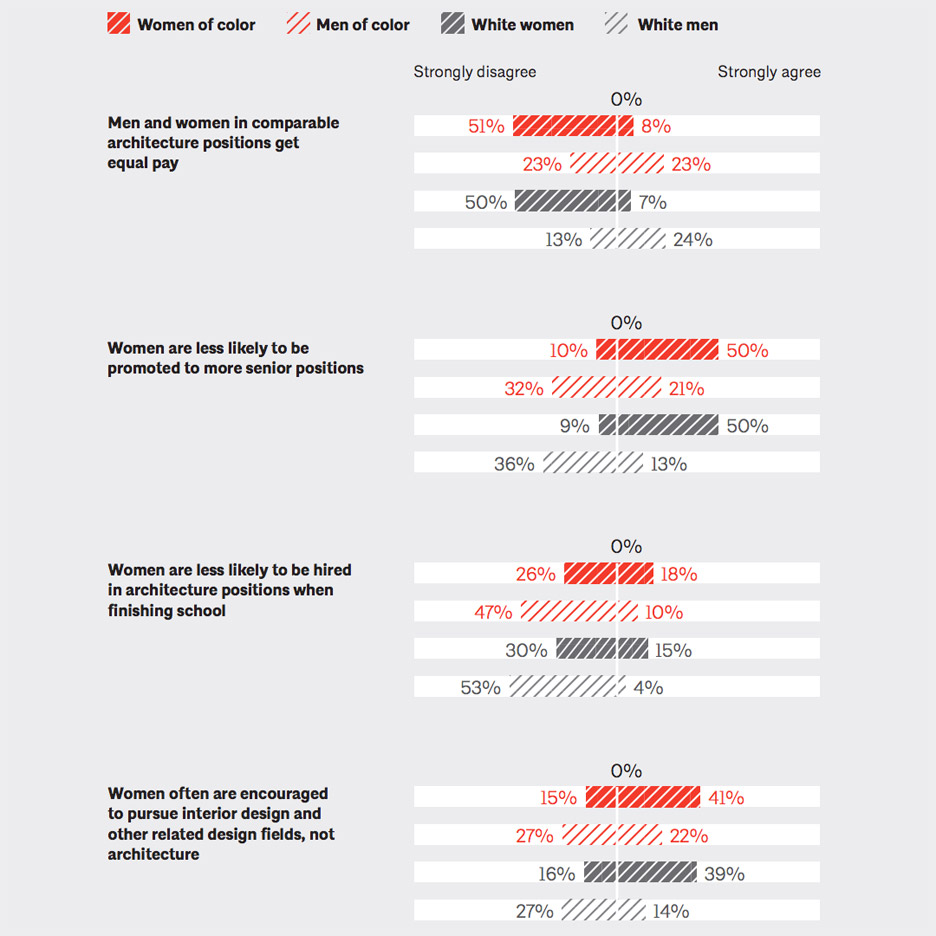

Half of all the female respondents also said that women were less likely to be promoted to senior positions within the profession.

Equal pay, which has been the focus of a number of high-profile campaigns in both the US and UK, was also still a serious issue in architecture, with 50 per cent of women reporting that women were less likely to be paid the same as men for the same role.

But less than half of male respondents felt that women were underrepresented, and even fewer felt that women were given unequal pay or were less likely to be promoted.

The vast majority of all the respondents agreed that people of colour were significantly underrepresented.

"Unlike with gender, both whites and people of colour clearly agree that people of colour are under-represented in the industry," said the AIA in its survey report. "Architects, industry leaders, and member associations could support a strategy for attracting people of colour to the profession."

"As for bolstering representation of women architects in the industry, a strong commitment and strategy will be required to overcome possible resistance from those that don't believe it to be an issue."

The survey polled opinions on the representation of gender and race within the profession from more than 7,500 architects, architecture students who were studying or who dropped out, and people who had previously worked in architecture in 2015.

It is the AIA's first major survey on the subject in 10 years and was conducted in 2015 as a joint project with six other US national architecture organisations. The results have now been published in an official report.

"There is plenty of anecdotal information that suggests there has been progress in building a more diverse and inclusive profession," said AIA president, Elizabeth Chu Richeter. "Yet, the information is just that — anecdotal."

"We need data, not anecdotes. We need reliable, quantifiable, and verifiable data."

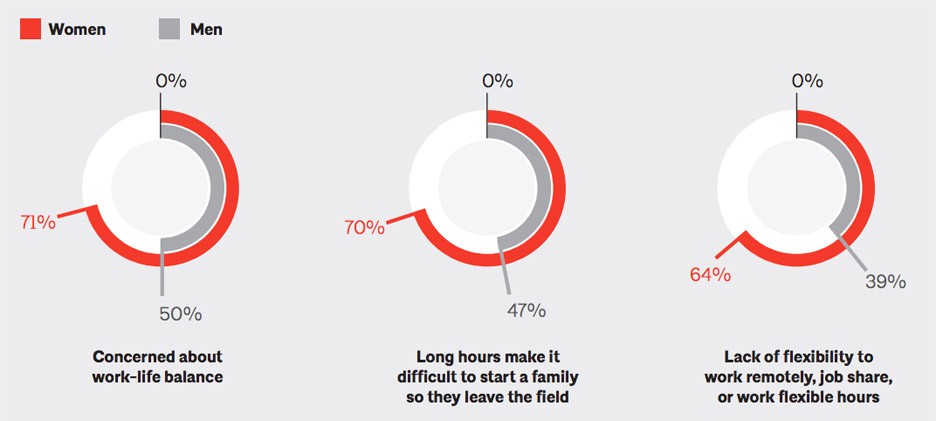

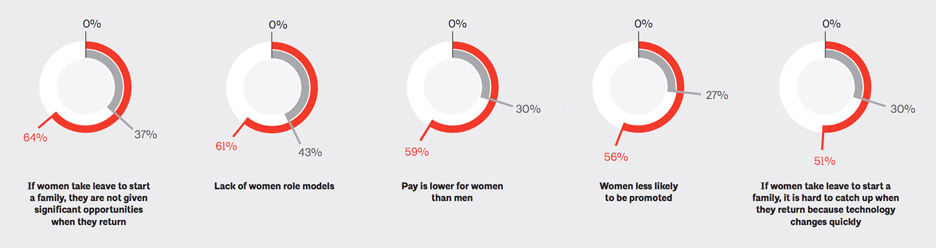

The survey also asked both women and men why they thought there weren't more women in architecture.

Seventy per cent of female respondents said long hours made it difficult to start a family, 71 per cent blamed concerns over the work/life balance made possible by a career in architecture, and 64 per cent blames a lack of flexibility to work remotely, job share, or work flexible hours.

"It is notable that all architects (regardless of gender or race) consider work/life balance important, and many have low satisfaction with their ability to achieve it," said the AIA.

"This is one of the most important areas where associations could lead an effort to change the professional culture. Not only would it address one of the primary concerns of women in the industry, but also it would benefit the field as a whole."

Another major factors cited by women was a lack of female role models.

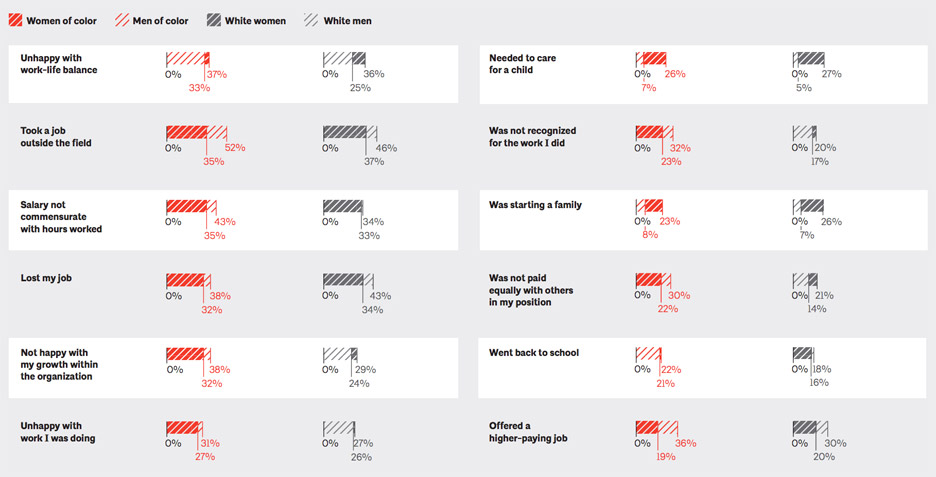

Of the respondents who had left their jobs, more than a quarter of the women said they had left to care for a child compared to less than 10 per cent of the men.

Men were significantly more likely to have taken another job outside of the profession or have been offered something better paid.

But white men were 10 per cent more likely to have been made redundant than white women, while men of colour were six per cent more likely to have lost their job than women of colour.

"We have made progress but not fast enough," said Chu Richter. "We have a great opportunity now to look at how to achieve the equity, diversity, and inclusion in AIA member firms through a creative means and provide a framework for the profession to act faster and better to meet a growing demand for architects."

The results come on the heels of the fifth annual international Women in Architecture (WIA) survey, which found that one in five women would not encourage another woman to start a career in architecture.

Of the 1,152 women surveyed worldwide, 72 per cent said they has experienced sexual discrimination, harassment or bullying within architecture – up from 60 per cent in 2015 – and 12 per cent said that they experienced discrimination monthly or more often.

Over 80 per cent of the female respondents also felt that having a child was a significant disadvantage for a woman pursuing a career in architecture.

The results of the WIA survey were published to coincide with the naming of French architect Odile Decq as the recipient of this year's Jane Drew prize for raising the profile of women within architecture.

This year Zaha Hadid also became the first woman to receive the Royal Institute of British Architects' Royal Gold Medal in her own right.

RIBA president Jane Duncan said the organisation was acting "to right a 180-year wrong".

"We now see more established female architects all the time. That doesn't mean it's easy," said Hadid.