Camps like the Jungle are "an important resource for all urban professionals to study"

Architects and planners should study refugee camps like the Jungle in France, according to architecture undergraduate Sophie Flinder, who has completed a dissertation on the way the camp has become a fully functioning town with its own culture (+ transcript).

Flinder, a student at Oxford Brookes School of Architecture in England, spent six months studying the history of the camp and charting how it has transformed from "a non-place to a place" as inhabitants, realising they would be there for a long time, started turning a squalid transit camp into a permanent home.

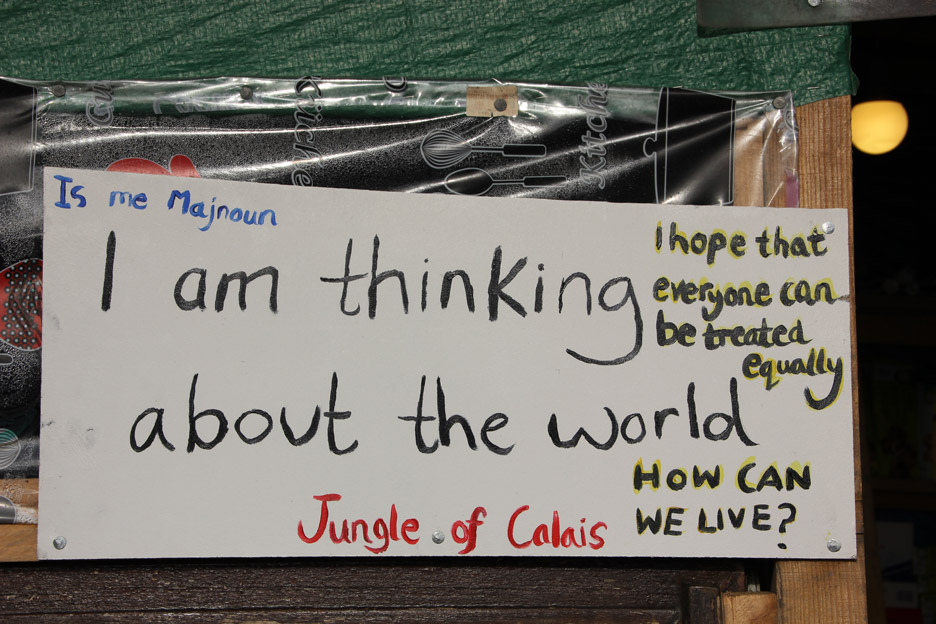

"What is built in the Jungle is based on the refugees' desires, memories and shared symbols," Flinder told Dezeen. "Shelter, religion, education, trading and culture are five clear aspects of any community and they are present in the Jungle."

Giant cardboard illustrated map of the #calais #jungle on the wall in the food distribution center pic.twitter.com/vws7L4I5GQ

— Jason Mitchell (@jjason_mitchell) December 21, 2015

Flinder had to hurriedly rewrite her dissertation when French authorities started demolishing the Jungle earlier this year, but she believes that architects could learn from the camp to help aid organisations build better camps in future.

"While the Jungle has poor sanitary conditions but a unique culture, official camps driven by [UN refugee agency] UNHCR are in much better shape but often stripped of identity," she said.

"It is also important to remember that the people living in these squalid conditions used to live in proper homes, and aim to do so again. Therefore I believe that architects and designers and their ability to think of transformable solutions should be included in the process of making shelters for these camps."

She added: "Shelters should be designed to break up daily routines, and give the user the freedom to individually inhabit the space."

Writing for Dezeen earlier this week, architect Jeannie S Lee described her visit to the Jungle and called for "a fundamental rethinking" of temporary facilities for refugees fleeing conflict and natural disasters.

"Architects must play a role in the challenge of finding a successful solution that bridges political acceptability, economic feasibility and humane decency," Lee wrote.

Last year humanitarian-aid expert Kilian Kleinschmidt told Dezeen that refugee camps are "the cities of tomorrow" and called for a new approach to such settlements.

"We're doing humanitarian aid as we did 70 years ago after the second world war," Kleinschmidt said, describing the approach of organisations like UNHCR as building "storage facilities for people."

Below is an edited transcript of the interview with Sophie Flinder.

Marcus Fairs: Tell us about yourself.

Sophie Flinder: I'm Sophie Flinder and I'm 22 years old. I'm from Oslo, Norway, and I'm currently living and studying RIBA Part 1 in Oxford. I will graduate from Oxford Brookes School of Architecture in May 2016.

Marcus Fairs: Why did you decide to do your dissertation on the Jungle?

Sophie Flinder: I read about the camp through the increased media attention of the migrant crisis over the summer. There were some great pictures of the structures; you could understand their function of even though they did not look like how we usually see them: the church looked like a church made out of tarpaulin and the school was graffiti-painted with "L'École".

However the news articles mostly focused on the riots and the growing number of people attempting to get to the UK, whereas I was interested in the people and their eagerness to adapt and learn.

Marcus Fairs: What is the Jungle and why is it different from other camps?

Sophie Flinder: Most refugee camps we see in the media are officially run by humanitarian organisations such as the UN and the Red Cross. The Jungle is an unofficial refugee camp in Calais, northern France, built by refugees, for refugees, with continuous opposition from the French and British governments.

Marcus Fairs: >Why Calais?

Sophie Flinder: Calais is located at the narrowest point on the English Channel and the main ferry port between France and the UK. It has always been an attractive place for migrants wanting to cross over to the UK.

Marcus Fairs: Describe the camp in urban terms. What does it contain and what is it built of?

Sophie Flinder: It is easy to talk about the Jungle as a town as it has clear boundaries and facilities you would find in cities, such as doctors, schools, places of worship and even nightclubs. It has a shopping street, libraries and a hotel.

If you include the amenities provided by volunteers the camp is more or less self-contained, covering the refugees' basic needs as well as offering opportunities to create a daily life. The busyness of the Jungle's very own shopping street is similar to other high streets on a Saturday.

The density of the Jungle has wiped out the national divisions within the camp, making it a more multicultural society, while different groups are evident through names of businesses and places such as Afghan Square and the Eritrean Nightclub.

But there are no such things as architects, urban planners or engineers. What is built in the Jungle is based on the refugees' desires, memories and shared symbols. Shelter, religion, education, trading and culture are five clear aspects of any community and they are present in the Jungle.

The structures in the camp are built mainly from found materials or materials given by volunteers passing through Calais. To keep safe from rain and wind, the best materials to use are tarpaulins and wood.

Marcus Fairs: What's the history of the camp?

Sophie Flinder: The Jungle started out as a vague term for the squats that started to appear in Calais after the closure in 2002 of the Red Cross migrant centre in nearby Sangatte.

Back then, smaller illegal squats, often divided by nation and religion, were spread over a large area of scrub between the woods and the sand dunes, getting little attention from the media and the authorities. However, the increasing number of refugees caused tension between the France and the UK due to questions of responsibility, and squats were frequently raided or demolished. In 2009 the Jungle, which housed 1,500 refugees, was bulldozed. Since then, smaller camps have continuously appeared around Calais.

In 2015 all the squats were merged into one defined area next to the newly opened Jules Ferry centre, the first official refugee centre since Sangatte. The centre accommodated 500 women and minors and provided access to toilets and showers for others that were squatting in the surrounding area, which was the only place refugees were tolerated by the authorities. This psychological border line around the tolerated area made it possible to draw the Jungle's size and location on a map, which gave the external world a clearer image of what to associate the Jungle with.

In March 2015 there were around 2,000 refugees in the Jungle. Since they were relocated into one collective camp the different nationalities and religions settled in different parts of the new camp and their identity got expressed through structures and ornamentation.

The Jungle was always a temporary place of residence. But due to the immigration influx to Europe over the summer, the Jungle got extremely dense, erasing the lines between nationalities and religions. There were around 7,000 inhabitants at its peak in December 2015. The enlarged number of inhabitants led to increased media attention, leading to more volunteers going to Calais.

Meanwhile the immigration influx to France resulted in strict surveillance of borders, making it harder for inhabitants to cross over to the UK, and the refugees had to reconcile themselves to staying in the Jungle for a long time. As a result, the term "temporary" no longer had a limitation in time.

In addition, since the camp was now being "tolerated" by the authorities, there was less chance of unannounced demolition and raids. The refugees, together with volunteers, had the opportunity to build a worthy society with structures and recreational activities that would break these daily routines.

If the refugees knew that they would reach England or get asylum in France tomorrow, the effort in each structure would probably not be there. From being a place that would fulfil the basic function of shelter while attempting to go to the UK, the camp started to fulfil the needs of life.

Marcus Fairs: How would you describe life in the camp?

Sophie Flinder: Both the French and British authorities have been pushed to improve sanitary conditions and access to emergency services. This infrastructure makes it easy for the external world to perceive the refugees' daily life as dignified. However, there are certain shortages, and the reality is that it is a slum. Also, a massive fence surrounds the camp separating it from the highway and the lorries heading for the UK, and therefore it takes away the freedom of movement you would find in a normal society.

Marcus Fairs: Talk about your dissertation. What were you trying to achieve with it?

Sophie Flinder: The title of my dissertation was "The Jungle – from non-place to home", and it was a study of how humans create space according to their needs and desires. French anthropologist Marc Augé described a non-place as a place stuck in the present, where history, identity and relations are non-existent. I felt like this was the perfect definition of the Jungle as it was back in 2003, where the place was hardly controlled by the authorities and therefore the refugees only used the space for short-term shelter before continuing their journey to the UK.

However, as the amount of time a refugee had to spend in the camp increased over the past decade, the refugees started to create structures that could enrich the time spent in Calais. I was interested in studying how interaction between the inhabitants and their relationships changed the urban space of the Jungle from being a non-place to becoming what I would call a society and a home in 2016. By using philosopher and sociologist Henri Lefebvre's "spatial triad", I examined the dialectical relationship of the lived, conceived and perceived space to understand how this space developed into being much more than a non-place.

Marcus Fairs: How did the camp transform from a non-place to a place?

Sophie Flinder: Due to the longer-term stays, the refugees now have to create a physical life while in Calais, and therefore structures such as shops and event spaces popped up. These structures give the refugees the opportunity to socially interact with each other, and focus on something other than their journey. Through stage performances and poem writing, refugees can tell their dramatic stories, and their stories gain an interest that wouldn't be present in a non-place.

The community feeling that is created in the Jungle has also created common areas where inhabitants independent of age, nationality and religion can socialise based on their personal interests, and by that the identity of the refugee will therefore play a role in the Jungle. Through language lessons and trading, the inhabitants can prepare for their life after the Jungle, and life in the Jungle is therefore no longer stuck in the present.

Marcus Fairs: What is happening in the camp now?

Sophie Flinder: In January 2016, semi-permanent accommodation was offered to around 1,500 refugees in the shape of 150 shipping containers. This was the beginning of the clearance of the whole Jungle. The goal for the French government is to have no more than 2,000 refugees in Calais, and these days all structures built by the refugees for the refugees are being demolished.

The containers provide basic facilities such as heating and bunk beds, but in order to be transferred to the container a refugee needs to be finger-scanned in France, which basically means that if they escape to the UK they will automatically be sent back to France. The loss of freedom, together with the loss of activities they have created in the Jungle, has made many refugees refuse the move.

Marcus Fairs: How is this affecting the culture of the camp?

Sophie Flinder: I have heard in an interview that some refugees referred to the container as jail. I definitely agree. Even though the containers provide heat and safety, the freedom is lost. Together with volunteers, refugees created structures that improved the social relations between the refugees regardless of age, nationality and religion. This has provided the Jungle with its very own unique society and a culture that I believe will now be lost.

Marcus Fairs: How did news of the demolition of the Jungle affect your dissertation?

Sophie Flinder: I ended my dissertation by saying that due to the news of the camp's demolition, the dissertation may have to be rewritten. And sadly that's what I had to do! Due to the demolition plans, I had to make changes to the text all the way up to the hand-in on 30 January.

At that time, I thought that the shops and schools would remain, but now I read that the only structures that will survive the demolitions is the places of worship out of respect. I concluded my revised dissertation claiming that now that all the unique structures that housed activities other than the repetitive moments of pray, eat, sleep are being removed, it is turning back to the constant limbo that is sign evidence of a non-place.

Marcus Fairs: What lessons does the camp have for architecture and urbanism?

Sophie Flinder: For me, unofficial camps like the Jungle seem like an important resource for all urban professionals to study. The Jungle is a real-life symbol of people's desires, needs and priorities. It is the people's imagination and wishes that control this space, and there is no such thing as building regulations, architects or engineers. It is common knowledge that gets built. And I believe that camps like these will teach us a lot.

Marcus Fairs: How can architects and designers help improve the situation for migrants and refugees?

Sophie Flinder: A long-term solution outside the camps is definitely needed, as the already existing housing crisis in Europe will reach another level that is hard for us to imagine We should concentrate on efficiency and sustainability through adoptable architecture.

Meanwhile, there are actions that can be carried out to make life better in camps. While the Jungle has poor sanitary conditions but a unique culture, official camps driven by UNHCR are in much better shape but often stripped of identity. I think a mix between the two would be the best.

It is also important to remember that the people living in these squalid conditions used to live in proper homes, and aim to do so again. Therefore I believe that architects and designers and their ability to think of transformable solutions should be included in the process of making shelters for these camps. Camps should provide the authorities with effective ways of managing the camps as well as it should be designed for individual people with different daily routines that need different kinds of space.

Money is of course always an issue, but shipping containers stripped of identity seem quite depressing. It should be looked at as something other than a machine for transit. Shelters should be designed to break up daily routines, and give the user the freedom to individually inhabit the space.

Photography is by Flickr user malachybrowne.