"Illustrations have become a key component of the response to terrorist atrocities"

Opinion: in the aftermath of the Brussels attacks, Rob Alderson asks how illustrations like Plantu's hugging flags and Jean Jullien's Peace for Paris symbol have become part of our "post-terror grammar".

After the news and the shock, come the cartoons. For a while I have been interested in the role illustration has come to play in the aftermath of major events.

From the terror attacks in Paris (at the Charlie Hebdo offices in January and across the city in November) to the death of David Bowie, it seemed remarkable that illustrations – rather than photographs or film footage – came to define these stories.

Just days before I was due to file this article, I got a real-time insight into this tragic phenomenon, when terrorists attacked Brussels' airport and Metro system, killing 31 people. The journalist and art critic Josh Spero tweeted: "It is sad, alarming and problematic that we are developing a post-terror grammar: a significant cartoon, colouring the lights, common hashtags."

Sure enough the cartoons came in droves – weeping Tintins, various defiant versions of the city's Manneken Pis statue and, most notably of all, the French cartoonist Plantu's image of a tearful French flag consoling its distraught Belgian counterpart. This, quite quickly, became the unofficial illustration of the tragedy.

As Spero noted, illustrations have somehow become a key component of the response to terrorist atrocities. This seems to be a relatively modern development, but of course the artform has long been associated with sober social, political and cultural commentary.

William Hogarth used visual satire to critique 18th-century London while the likes of James Gillray, Thomas Rowlandson and George Cruikshank spearheaded the booming industry in scurrilous imagery that followed. Once crowds would throng the windows of print shops to peruse the latest broadside. Later these would be incorporated into magazines and newspapers in a tradition that endures to the present day (Plantu's cartoon was published in French newspaper Le Monde).

So serious illustration has a serious pedigree. This pedigree has been furthered by some fantastic artists too – see Art Spiegelman's graphic novel Maus, Marjane Satrapi's animation Persepolis or the reportage work of Olivier Kugler, George Butler and Molly Crabapple. The New Yorker of course is famous for its illustrated covers and it is eagerly looked to whenever a major event occurs. The black-on-black silhouette of the Twin Towers created by Spiegelman and the magazine's art director Françoise Mouly after 9/11 is rightly considered a classic. But I don't think that image defined the event in the way we have become used to in the last 18 months.

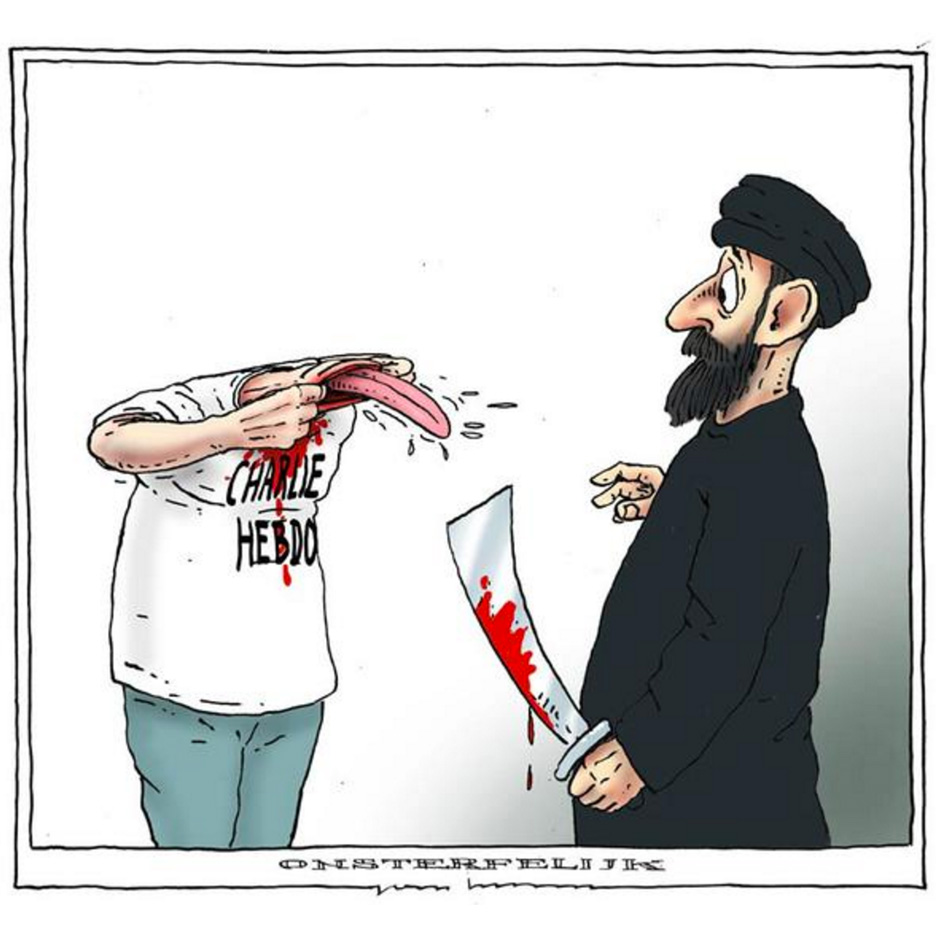

The story of the rise of illustration in this scenario starts, I think, with the Charlie Hebdo attacks. Cartoons had been created in response to terrible events before – in fact it's interesting to note that in the aftermath of the Japanese earthquake of 2011, Dick Bruna drew a weeping version of his famous Miffy rabbit, echoing the motifs we have seen recur with Tintin.

But when terrorists attacked the Charlie Hebdo offices in January 2015 they attacked a magazine that revelled in the power of the illustrated image. Not surprisingly, illustrators the world over reached for their pens in pain and protest. There was perhaps not one defining image but a slew of illustrated responses – the ones I remember most are Dave Brown's bird-flipping newspaper in The Independent, and Jean Jullien's simple depiction of a pen being jammed into the barrel of a rifle.

When terrorists struck again in Paris in November, Jullien again reacted as creatives are wont to. He dashed off a sketch of the peace symbol combined with the Eiffel Tower and posted it on his Instagram. The response was colossal (to the artist's evident embarrassment). Peace for Paris, as it became known, was adopted by millions of people as a defiant symbol of hope during the days that followed. It was painted on faces, recreated by crowds in public places and projected onto public buildings.

And so to this week, to the awful events in Belgium and to Plantu's popular cartoon. As Spero says illustration has become part of the process now – but why?

I would suggest four possible explanations, and I think that a combination of all them might be in play. Firstly, and perhaps most obviously, modern technology allows illustrators to create and share their work with enormous speed and potential reach. Some people are uncomfortable with what they perceive to be artists jumping on the bandwagon of terrorist attacks, but as I have argued before, it's perfectly natural for them to react in the medium in which they are most comfortable.

Secondly, I believe our general attitude to illustration as an artform might be changing. The extraordinary rise of the adult colouring book has perhaps shifted the way we think about illustration, and at least loosened it from its longstanding connotations as a childhood form.

Thirdly, I think illustrators have become more interested in using their skills in different ways. There was a time, not that long ago, when illustration seemed condemned to irrelevance, as practitioners embraced the kind of tea-towel-twee with which we are all familiar. As Lawrence Zeegen, dean of design at London's Ravensbourne college, put it recently: "Surely it must be time for illustration to get real and recognise the power of the illustrated image to say something about the world in which we live? We all need our lives brightening up, of course, but personally I still yearn to see work with meaning, with attitude and with the ability to make the viewer think."

I think illustrators are increasingly heeding his call, and the examples of Charlie Hebdo and Peace for Paris have shown there is an appetite to be catered for (again I am aware some would put this in more cynical terms).

And finally, I think we have rediscovered how powerful this kind of illustration can be. It leaves room for interpretation in a way that a photograph does not, and in the wake of confusing and complex events, viewers can engage more easily with a medium that meets us halfway.

Illustration communicates on an emotional rather than an intellectual level; in simplifying ideas and emotions it hits us in the gut (as Françoise Mouly would say). And online, where gut feeling wins out over cold analysis every single time, is it really a surprise that illustration has assumed such cultural significance?

Rob Alderson is managing editor of WeTransfer and a freelance arts and design writer, based in Amsterdam. Previously he was editor-in-chief of It's Nice That.